The Tunesmith, Part 1

“Getting to Know Moe”

If you aren’t familiar with the composer Maurice Jerome, you aren’t alone. He spent most of his career writing songs for lesser films at Warner Bros., and only occasionally placed a number in a top picture like Casablanca. (No, he didn’t write “As Time Goes By,” he wrote the other song Dooley Wilson sings in the movie, “Knock on Wood,” which I’ve always loved.)

But here’s the funny thing: dozens of his songs are known to folks of my generation through their placement in cartoons, as I elaborate in the essay below.

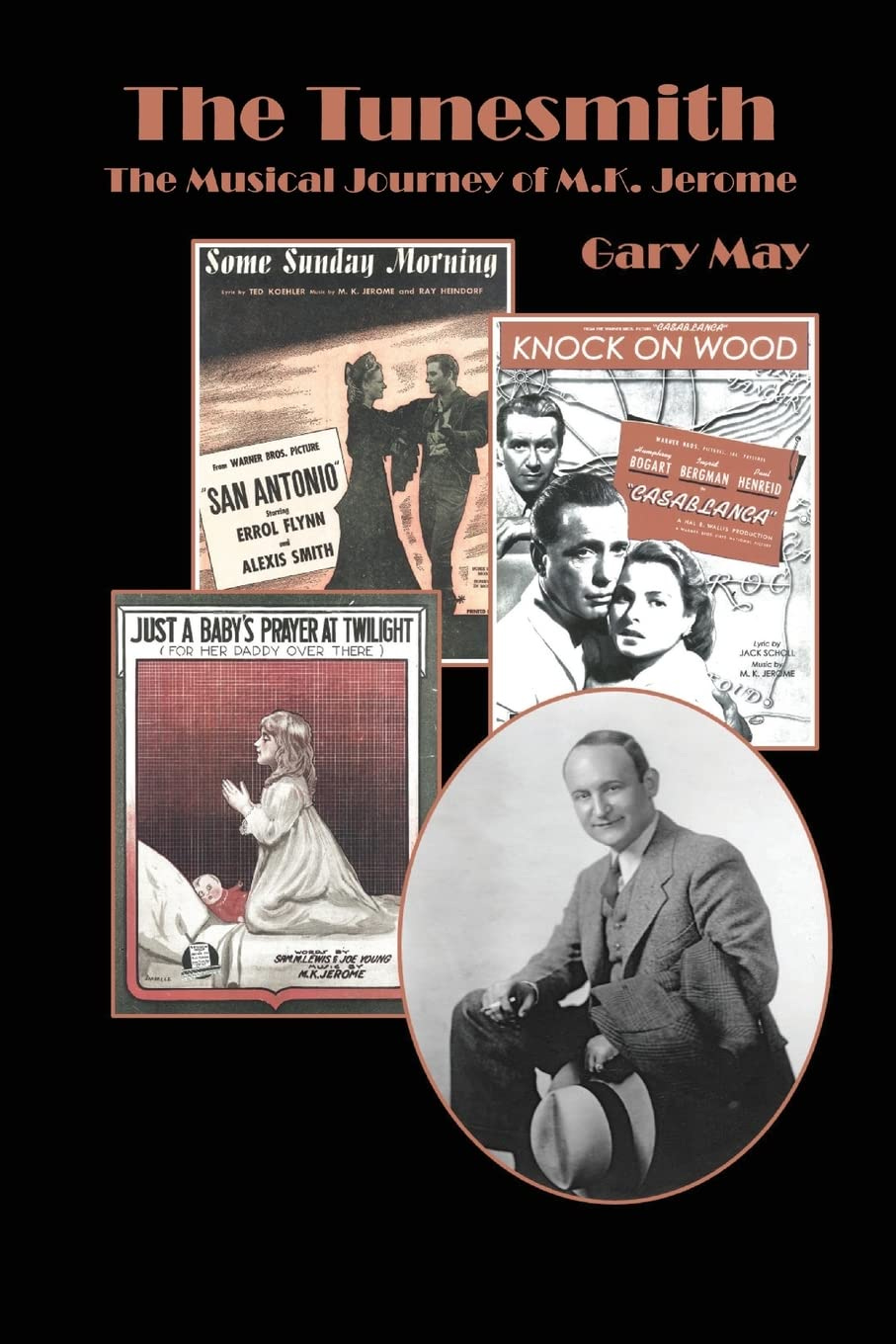

In recent years, “Moe” Jerome is at last getting some attention: a few months ago, his grandson, Gary May, wrote the biography of the songwriter, which he has poetically titled The Tunesmith: The Musical Journey of M.K. Jerome (available on Amazon).

Even more notably, the legendary singer-songwriter James Taylor included one of Jerome’s songs, “Easy as Rollin’ off a Log,” on his 2020 album, American Standard. It turns out that Taylor - who was said to be inspired to write his classic “Sweet Baby James” by Jerome’s 1937 western lullaby, “My Little Buckaroo” - also grew up learning songs, both classic and obscure, from watching old cartoons on television. Who knew?

(This essay is my contribution to The Tunesmith. my thanks to Gary May for encouraging me to also publish it here. This week (Saturday September 16) on Sing! Sing! Sing! I’m doing a special tribute to Moe Jerome and his songs, from the teens to the 1950s, including an interview with Gary. Info on how to tune in to Sing! Sing! Sing! may be found below, or for an advance listen, click here. Very special thanks to Elizabeth Zimmer for her invaluable and much-need proofreading.)

“Getting to Know Moe”

In 1988, the author and minister Robert Fulghum wrote “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten.” In the generation that grew up in the 1970s, most of us learned all we really needed to know about music before we were ten years old. However, neither kindergarten nor any other kind of formal education had anything to do with it.

Most of us born in the 1960s and earlier grew up watching vintage Hollywood cartoons, mostly produced 20 to 30 years earlier. As a generation, we collectively devoured the antics of Bugs Bunny and Betty Boop - but, unbeknownst to us, we picked up on a lot of other kinds of culture as well. That was especially true for music: even as kids, many of us realized that the soundtracks of vintage cartoons were a literal education in great music, touching on at least three separate areas: jazz, the Great American Songbook, and the European classical tradition. Virtually everyone of my generation can chalk up his or her first exposure, not only to Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong, but to Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen, not to mention Liszt, Rossini, and even Wagner, to these miraculous seven-minute short films that were essentially considered throwaways when they were new.

This kind of education by osmosis works in precisely the opposite fashion of a formal education; in formal education, you start with the first or most important examples of something and work your way from there. If I were teaching a course on the great American songbook, I would start with George Gershwin and Cole Porter. But as it actually happened, we knew the songs of Maurice Jerome - aka M. K. Jerome - aka Moe Jerome - though not his name, well before we had ever heard of the music of Richard Rodgers. I can pretty much guarantee you that I walked around the streets of Brooklyn singing “Some Sunday Morning” well before I knew the words to “Blue Skies” or “The Man I Love.”

In this aspect of his music, M. K. Jerome has a lot in common with Raymond Scott, in that neither of them ever composed any music specifically for animated films. Still, because of almost random circumstances, cartoons somehow became the channel through which their music reached later generations.

Warner Bros. employed Jerome as a contracted songwriter. This was a reasonably well-paid position - you got a weekly salary as well as royalties - but with absurdly little power. It was only on Broadway, and especially after the war, that composers had at least some degree of control as to how and where their music was used. Their Hollywood counterparts, however, had absolutely no control whatsoever over the destiny of their work. The studio songwriters were required specifically to write on call; sometimes they were given a specific plot or at least a genre - western or gangster movie or whatever - and sometimes they had the voice and personality of a specific star in mind. But often, they just wrote completely generically, a love song that could be sung by any glamorous singer male or female standing in front of a dance band, a comic number for any funny person, or a lullaby meant to be sung to a child.

The use of that music in those cartoons wasn’t even an afterthought. The studios regarded the songs that they published and owned as a very specific kind of asset, meant to be utilized wherever it made the most sense commercially. Songs commissioned for one project might be dropped, then be used somewhere else. Often it was a case of traveling down the food chain: a song cut from a major motion picture might turn up in a B-movie, or, failing that, a short subject, or, if it reached the absolute bottom of the food chain to the studio, a cartoon. But conversely, in a way that no one could have predicted during the heyday of the studio era, exposure in these classic cartoons often does more for a song’s long term recognition than even placement in a hit A-movie.

At the start of the talking picture era, the big studios started to acquire whole divisions that they had never thought of before. In addition to sound and music recording facilities, they also gradually built up music publishing operations and a cartoon department, and typically the two were linked together. For much of the ‘30s, if the moguls thought about cartoons at all, they didn’t think of them as animated equivalents of comedy shorts, i.e., what Hal Roach was concurrently doing with Laurel & Hardy, but as low-budget mini musicals, more like what Warners was concurrently doing with its live action Vitaphone shorts.

Up at least through the mid-to-late 1930s, most cartoons were primarily musical, but a decade later, by WW2, they were more specifically comedy-driven with occasional - and highly valuable - musical interludes. At the moment when Jerome and Jack Scholl wrote “My Little Buckaroo,” the cartoons themselves were in a period of transition. The Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies were independently produced by Leon Schlesinger, but for all intents and purposes were Warner Bros. productions - and their central connection to the features and other films released by the big studio was, in fact, via the music, in the way that songs written for their major films would also be featured in the cartoons.

# # #

“My Little Buckaroo” was one of Jerome’s bigger hits of the 1930s. It was written for The Cherokee Strip, a 1937 Warners B-western (all of 55 minutes long) in which it was sung by Dick Foran. Foran was then being billed as “the singing cowboy,” a category in which he would quickly be eclipsed by both Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. Foran had the face of a basso but a voice that was closer to a tenor, and he sings the song with appropriate sincerity in a campfire sequence. “My Little Buckaroo” was part of a trend of lullabies of that era, which also includes “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride,” another western-themed lullaby, and “Little Man, You’ve Had a Busy Day,” all three of which turn up, in one form or another, in Warners cartoons of this period.

“My Little Buckaroo” was popular enough to be recorded by several important dance bands, among them Russ Morgan (Brunswick), Joe Haymes (the ARC labels, including Conquerer), Johnny Hamp (Bluebird) and singer Dick Robertson (Decca); still, the most important version by a long shot was by the biggest superstar of the entire era, Bing Crosby (Decca).

It was probably Witmark, Inc., the song’s publisher (a key part of the Warner Bros. music empire), who decided to give “My Little Buckaroo” a further push by making it the focus of a 1938 entry in the Merrie Melodies series. You can tell that by 1938, director Friz Freleng and the rest of the staff are keen to move away from “pure” musicals and towards comedy; the one-reeler is essentially a genre parody, making fun of all the tropes of westerns. It’s essentially the same in content as the great cartoon westerns of the 1940s, except that the timing is not quite there yet - the gags are much more slowly paced and thus much less funny than they would be a few years later, especially in the masterful genre parodies of Tex Avery.

My Little Buckaroo (sometimes spelled “Buckeroo”) is a basic western plot, most of which is a good guy chasing a bad guy. The major parodic element is casting a caricature of the radio-and-film comedian Andy Devine (in the form of a pig) as an unlikely hero. He sings only eight bars of the song (according to Keith Scott, director Fred “Tex” Avery supplies the voice), and that’s enough; as he croons in an impersonation of Devine’s scratchy caterwauling, even his horse winces in pain. This is an example of the comedy overpowering and even killing the appeal of the music - and not even being all that funny to begin with.

As historian Jams Parten points out, the song is better served in Dog Daze (1937), which is essentially a collection of what Joe Adamson labeled “spot gags” revolving around matters canine. It’s essentially a plotless parade of one dog joke after another, but the musical highlight is a trio of prairie dogs rendering a very slick period close harmony version of “Buckaroo.” Jerome must have been happy that the song was given such a prominent spot, even though somebody felt the need to change the lyrics - it’s now a generic western song rather than a lullaby - and, in the process, also omit the title.

As it happens, the song’s best on-screen placement isn’t in a feature or a cartoon at all, but in the delightful 1940 live-action one-reeler Cliff Edwards and his Buckaroos, written by future TV mogul Nat Hiken and directed by the stylish Jean Negulesco. Here, we get a full chorus of “Little Buckaroo” by the legendary “Ukelele Ike” accompanied by a cowboy choir - proving that the song was still being heard in 1940. Another song by Jerome and Scholl from the Edwards short also appears in a number of Warners cartoons, such as their humorous adaptation of a traditional cowboy air, “I Can’t Get a Long Little Dogie.” Daffy Duck sings this in A Coy Decoy (1941) - ironically right after Porky Pig does a memorable though brief version of the other cowboy lullaby, “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride” - another cowboy lullaby, this one by Johnny Mercer and Richard Whiting.

to be continued (and concluded).

For an advance listen to the Moe Jerome episode of Sing! Sing! Sing!, which is airing this Saturday on KSDS San Diego (more info below) click here.

Disclaimer: These are my memories of these incidents, nothing more, nothing less. I apologize in advance in case they may not line up precisely with anyone else’s account of what transpired on those occasions.

Special Thanks to Elizabeth Zimmer (hooray!) for pitching in and scanning this two-part story for typos, mistakes, and assorted boo-boos!

A mistake all my own: in my quickly-written mini-post on Mel Tormé Swings Shubert Alley, I got one thing seriously wrong - the most-recently-written song on the album is, of course, “All I Need is the Girl,” from Gypsy. My bad.

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here.

Wednesday, September 13

7:00PM (EST) - THE NEW YORK ADVENTURE CLUB presents:

Legends of Lounge: The All-Time Great Jazz Pianist-Singers

Webinar

click here

Wednesday, September 13

9:30PM (EST) - Will Friedwald's CLIP JOINT presents:

THE MEL TORME 98TH BIRTHDAY SPECIAL

no cover charge!

click here

Four Episodes of Sing! Sing! Sing on KSDS (88.3 San Diego) spotlighting the life and legacy of Tony Bennett:

SSS 59 2023-08-12 Tales of Tony

SSS 58 2023-08-05 Tony Bennett sings the George & Ira Gershwin Songbook

SSS 57 2023-07-29 Tony Bennett - Van Heusen, Burke, Cahn, Styne, Sondheim, Comden & Green

SSS 5 2022-07-30 Tony Bennett @ 96: The Johnny Mercer Songbook

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more!

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

I don't think animation gets enough respect as a distributor and arbiter of musical taste as well as humor. You, being a scholar of both animation and music, would likely agree with me.

Fascinating!