Here’s the complete album in one file:

Here’s another new essay that I’m going to run here on SubStack before it goes into my forthcoming book, Nights at the Red Steinway: Adventures in Jazz Piano, which is (hopefully) going to be published later in 2024 by Backbeat Books. Extra special thanks - even more than usual - for the input of Bill Sando, of the American Pianists Association, and my chief editorial person, Elizabeth Zimmer.

Teddy Wilson (1912-1986)

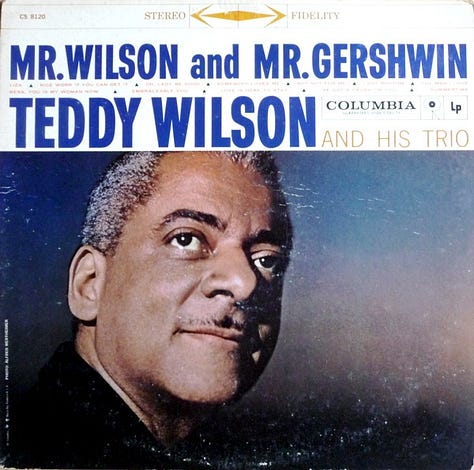

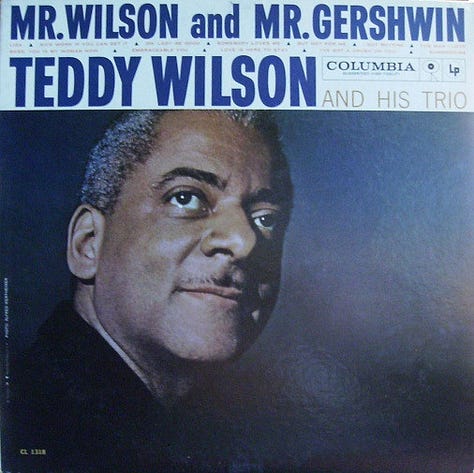

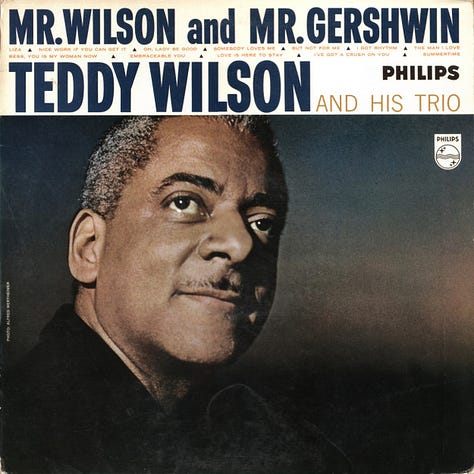

Teddy Wilson, Mr. Gershwin and Mr. Wilson (1959)

In 1934, when Teddy Wilson was 21 - and George Gershwin was 35 - he recorded his first date as a leader, a set of four solos, two of which were songs by Gershwin, “Liza” and “Somebody Loves Me.” “Liza,” in particular, would be a Teddy Wilson perennial; there are at least 20 versions in Wilson’s catalog, many from the 1930s alone. It would be Wilson’s go-to Gershwin song. (There’s an especially spiffy version from 1939, where he’s backed up by his own short-lived big band; in this version in particular, you can really hear his roots in Earl Fatha Hines.)

In 1959, Wilson recorded what would be his only major songbook project, Mr. Wilson and Mr. Gershwin. What makes this album special is that it’s a Gershwin collection from a great jazz musician who was playing those songs well within Gershwin’s own short lifetime. This is important for two reasons: as we know, Gershwin was himself a jazz fan, who acknowledged freely his debt to the great African American piano giants. And also because, shamefully, although Gershwin lived in one of the great ages of sound recording and even sound film, he left a painfully small recorded legacy. He was the most public-facing songwriter of his day, who starred in his own radio show at several points in his career, and he was never shy to perform, and yet all that survives of his playing are dribs and drabs.

It’s not much to extrapolate that Gershwin heard Wilson playing at least some of his songs—certainly, if nowhere else, as pianist with Benny Goodman’s trios and quartets. Even if Goodman hadn’t been part of the especially-jazzy pit orchestra on Gershwin’s Girl Crazy, Goodman was the central figure in all of pop music and jazz by 1935-’36 and Gershwin would have been well aware of that.

When we listen to this 1959 album, I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to suggest that Gershwin himself would have loved it, and that this was the way he might have wanted to hear his music played and even wanted to play it this way himself. Like Gershwin, Teddy Wilson (1912-1986) was a virtuoso player as well as a showman; Gershwin, unlike his close friend Oscar Levant, never played as a sideman with one of the major dance bands of the era, but the syncopated sound of 1920s hot music was in his bones. More importantly, it was in his songs - every beat of his music, in fact.

The modern piano trio - with bass and drums - didn’t really come into its own until after WW2; as natural as it seems, for most of the 1940s, many keyboardists were so enamored of the King Cole Trio that they emulated its piano, guitar, and bass format. Wilson wouldn’t have been working with the bass/drums trio until relatively late in his career. I personally enjoy Mr. Wilson and Mr. Gershwin not least because, other than adapting his playing to the relatively new format of the trio, that this is fundamentally the way Mr. Wilson was playing these tunes when Mr. Gershwin was still with us.

Throughout, Wilson’s style is firmly in the 4/4 swing tradition of the 1930s, rather than the two-beat we associate with the roaring ‘20s. Virtually every piece is in a swingingly staccato groove, and the image that comes to mind is dancing - the elegance and exuberance of one of the great African American tap dancers as well as that of fingers dancing across the keyboard. When Goodman and Wilson recorded a soundtrack for a Disney cartoon, the images included an abstract creature composed only of fingers for legs, literally dancing across an endless horizon of white-and-black piano keys.

The album opens with “Liza,” from the 1929 Ziegfeld production Show Girl. For years this was considered a classic Gershwin song, but it has been less frequently included in Gershwin projects over the last 60 years or so, perhaps because it was originally written for a minstrel-style number and was conceived as a sort of zippier, more up-to-date version of an old-style “plantation” song. Wilson’s version is particularly dance-centric; it’s reminiscent of the great song-and-dance man Avon Long, who was supposed to sing it to Lena Horne in a cut number from the 1945 MGM movie musical Ziegfeld Follies. Close your eyes: it’s hard not to visualize a dance act like the Step Brothers or the Berry Brothers going through their paces. Both bassist Al Lucas and drummer Bert Dahlander also seem to be dancing through their featured portions, which are more like breaks - dance breaks, in fact - rather than full-out solos. An exchange with Dahlander (on brushes) sets up a series of false endings which suggest, for all the world, a hammy dancer milking the applause and refusing to leave the stage, like Fred Astaire and Judy Garland at the end of “We’re a Couple of Swells.”

Speaking of Astaire, the collaboration between Gerswhin and the great dancer - two Broadway shows and two classic films (not to mention the 1957 Funny Face) - is a major subset of the Gershwin catalog. Surprisingly, there are only two Astaire-associated songs here, and they’re the next two tracks. Like “Liza,” “Nice Work if You Can Get It” (from A Damsel in Distress, 1937) and “Oh! Lady Be Good,” are also highly dance-driven. Lucas solos arco on the first, briefly quoting “Rhapsody in Blue,” and summoning up the image of a dancing bear.

A standard jam session ice-breaker, “Oh! Lady Be Good,” is one of many tracks where Wilson shows what he learned from Louis Armstrong, particularly after recording with the jazz giant in 1933. He starts playing with the tune and improvising melodically from the very first note. Dahlander sets it up with brushes, and then Wilson is off to the races. He says all that needs to be said in a brief two and a half minutes, and there’s even room for a solo by Lucas. Even the flourish at the coda again suggests a dance trio taking a bow.

Most of the other tracks frame the melody and then play with it in the same way. “Somebody Loves Me” shows what a great “singer” Wilson is - he captures the spirit of Buddy DeSylva’s lyric as well as any vocalist ever has, optimistic but guarded: looking for “somebody” but slightly reserved and somewhat guarded. Conversely, “But Not For Me” is a cheerful song about a sad situation, delivered with the wry, self-mocking humor that was Ira Gershwin’s trademark; his rationale seems to be, “well, I guess she’s not for me - so I might as well dance and have a good time.”

“I Got Rhythm” is a brief blowing number; at two minutes, including breaks by the bassist and drummer, it sounds like a “chaser,” something he might throw in to quickly conclude a night club set - in fact, it concludes the album’s side A.

We can’t know if it was planned this way or not, but there are more ballads and concert-style numbers on the second side. “The Man I Love” has always heavily suggested Gershwin’s concert pieces, in particular “The Rhapsody in Blue,” and Lucas has an especially compelling arco statement here.

There are also two numbers from another cornerstone of the Gershwin canon, Porgy and Bess (1935): “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” and “Summertime.” Although swinging, they also sound like a 1930s notion of jazz chamber music, which seems to be how listeners regarded any small group performance that wasn’t an out-and-out freeform jam session. Wilson’s phrasing on the former suggests the song’s relationship to Gershwin’s second prelude, and another arco bass solo further underscores the connection to classical music.

“Embraceable You” is sweetly melodic and vividly filled with ornamentation: cascades at the start, trills later. It’s almost like he’s accentuating lyricist Ira Gershwin’s idea of the “many charms about you” by illustrating those charms musically. The way Wilson accentuates the high notes on the word “embraceable,” then the lower notes on the bridge (“I love all those many charms about you…”) almost sounds like he’s engaging in a duet, or at least a call-and-response pattern, with himself. “Love Is Here To Stay” brings us back to what Variety described, back in the day, as “terp tempos,” with more dancing-bear bass from Lucas.

The bassist opens “I've Got A Crush On You” in the same fashion, though somewhat slower; this is the song (first heard in the 1928 Treasure Girl) that the Gershwins had written as a bouncy foxtrot, but which Ira later admitted sounded better as a slow ballad after hearing jazz singer Lee Wiley sing it that way. This version splits the difference, romantic enough, but with clearly-delineated rhythm such that you can picture dancers pirouetting about the ballroom floor; there’s a particularly precious pas-de-deux between Wilson, and Lucas, again playing arco, as he does in most of his solo statements here.

“Summertime,” which opens Porgy and Bess, is an interesting closer, wrapping up a great jazz album with a semi-classical note, particularly when Lucas, arco again, rephrases the melody to the accompaniment of Dahlander’s mallets, which suggest Vernel Fournier with Ahmad Jamal. It’s an effective synthesis of multiple strains of mid-century American music: jazz, opera, musical theater, social dance music.

There’s a famous story about George Gershwin going to 52nd Street at the height of “The Street”’s fame around 1936, and hearing the great jazz violinist, singer, and bandleader Stuff Smith. Smith and his men play one hot instrumental that has Gershwin particularly inspired and also perplexed; when he asks Smith about it, the violinist responds, “Why, Mr. Gershwin, don’t you recognize ‘I Got Rhythm?’” Gershwin would have easily recognized all 12 of his classic tunes here, and, to paraphrase what Ira Gershwin said about Ella Fitzgerald’s songbook album of the brothers’ music, Wilson would have made George Gershwin appreciate his own work even more.

Very Special thanks to the fabulous Ms. Elizabeth Zimmer, for expert proofreading of this page, and scanning for typos, mistakes, and other assorted boo-boos!

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here.

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

All of your sentences are rewarding, but I think my favorite is “Here’s the entire album in a single link.”

I just acquired a 2-record set of Earl Hines performing Gershwin. It's from 1977 on the Classic Jazz label. The producer was Franco Fayenz and the recording was made in 1973 in Milan. In the liner notes Fayenz recounts when Earl met George.

"Hines first met Gershwin at the Apex Club in Chicago, and was left with a clear and indelible impression. Hines was at the piano playing "Rhapsody in Blue" without accompaniment, when a stranger came up to listen to him very attentively. At the end he was complimented and told by this person that he had never before heard that piano version of the piece played so well. It was only later that Hines found out that he had talked with George Gershwin in person."

"Rhapsody in Blue" opens and closes the wonderful collection.