(Special thanks to Chuck Granata, of course, and to Michael “Contentious” Kraus and Rob Waldman for reading this through in advance. And as always to Elizabeth Zimmer!)

Most Sinatra fans were completely unaware of this performance until a few years ago when it surfaced on a very rare bootleg; the great saxophonist and clarinetist - and all-time Frank fan - Ken Peplowski was the first to share it with me. Chuck Granata was able to procure a superior source which he restored for a Sony Music Sinatra project, which, alas, has yet to be actually released.

As usual, I planned this essay for a single post on substack but it grew to the point where I decided to share it over several days during Sinatra’s birthday week. (As I do every year, I hereby suggest and even insist that everybody should wear something blue on the birthday of St. Francis of Hoboken, much as we all wear green for the birthday of that other, lesser saint - the Irish one. Henceforth, let the wearing of the blue become both a moral and a fashion imperative every year on December 12th.)

Somehow a notion has been unleashed upon the world that Sinatra only sang soft romantic ballads during the 1940s, and that he didn’t become a hard-swinging jazz singer until the mid ‘50s, when he launched his epic collaboration with the great Nelson Riddle at Capitol Records - what we call “Phase II” of his career.

Those of us who have written seriously about Sinatra over the years, including Chuck Granata, Jim Kaplan, and myself, have labored hard to put this notion to rest. Sinatra could and did swing from the very beginning - the Dorsey days at least - and did so consistently throughout the WW2 years and beyond. His major musical director, the underappreciated Axel Stordahl, himself rarely wrote uptempo arrangements in the 1940s, but assigned them to talented, big band-trained writers like George Siravo, Heinie Beau, and, on several occasions, Billy May.

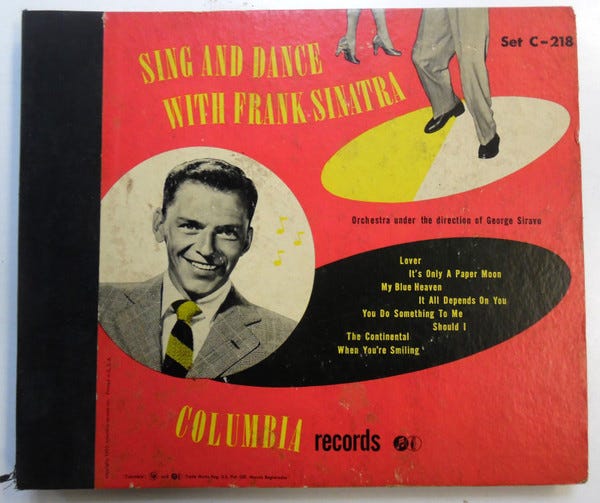

In fact, Sinatra’s first original long-playing album was a set of uptempo numbers, taped in early 1950, titled Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra. (Chuck has produced the definitive CD reissue, which also includes an authoritatively detailed essay about the production in his album notes). Throughout that year, he continued to regularly include faster tunes on his weekly CBS-TV series, and then, as the first season was coming to an end, in the spring of 1951 he left us with a rather amazing audio document that well-nigh proves that he was already very loose and swinging in his more mature manner well before he had signed with Capitol Records or had even heard the name of Nelson Riddle.

Not many people, now or especially then, realized this because, as is well-known, Sinatra was then on a downward slide, career-wise, what he later famously called his “year of Mondays.” It lasted longer than a year; he was between contracts at major movie studios, his decade-long relationship with Columbia Records was in its final months, and his CBS series struggled for ratings. (He was also in the middle of a brief run of a radio series titled Meet Frank Sinatra that was so obscure that we barely know anything about it.)

Perhaps ironically, even though his career was on the downslide, his actual voice itself was not. Vocally and health-wise, he had already hit rock bottom a year earlier, during the infamous engagement at the Copacabana, when he came down with a devastating case of laryngitis and had to cancel part of the run. Yet he recovered, and certainly by 1951 was at full power.

In the summer of 1950, he had played the London Palladium, but in the fall and spring, he was so busy with The Frank Sinatra Show and Meet Frank Sinatra that there was barely time for personal appearances. Then, in April 1951, he announced a two-week run at the New York Paramount Theater in Times Square, starting April 25. (Incidentally, the bootleg dated the performance from January 1, 1950, but clearly it’s from sometime during the two-week run at the Paramount in late April or Early May.)

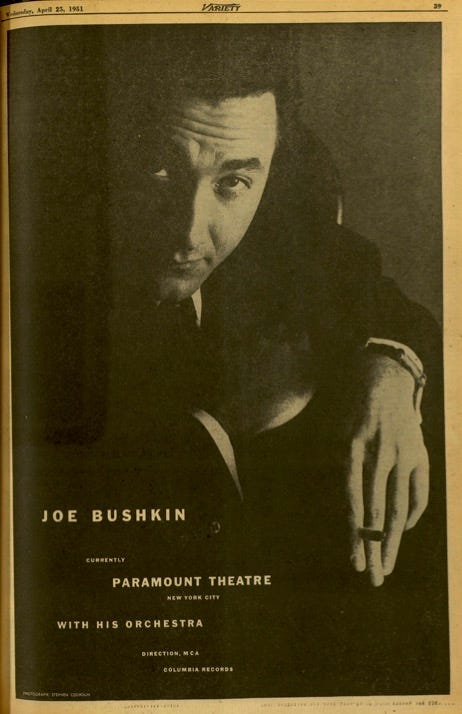

The rest of the cast included the popular pianist and Sinatra’s longtime pal Joe Bushkin, serving as guest star and musical director. Then there was the irresistibly perky 23-year-old singer Eileen Barton; the daughter of Sinatra’s publishing partner Ben Barton, she had started her career as the girl singer on Sinatra’s 1944 radio show but in 1950 landed her biggest hit, “If I Knew You Were Comin' I'd've Baked a Cake." A pair of comedians, Tim Hubert and Don Saxon, were also on the bill. Except for a few bars of Bushkin here and there, we don’t hear any of them on the 20-minute aircheck.

However, we do get to hear the larger-than-life female comedian Dagmar, who was then making a splash, as Variety would say, on the early TV talk and variety program Broadway Open House. At this moment in time, Dagmar was, quite possibly, almost as much of a draw as Sinatra. (More about her later.) Near the end of the run, most of the cast - Bushkin, Barton, and Dagmar - appeared with the singer on his CBS show, and between the four of them, gave us one of the more memorable episodes of that series. Sinatra was paid $22,500 for the first week, which dropped to $22,000 for the second, which was the same as Frankie Laine, and considerably less than the $50K that Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis were making for their Paramount appearances at around the same time. (Variety, April 18, 1951)

Despite how this was Sinatra’s “first live appearance in six months” (Kaplan), and, as papers noted at the time, his first show at the Paramount in six years, the reaction and the box office were, to say the least, underwhelming. As always, the live show went on between screenings of a movie; in this case, it was Forbidden Past, starring, coincidentally, Ava Gardner, whom he would marry in November of that year. (Variety noted that Sinatra and Gardner were “romantically linked.”) The papers (specifically the Daily News and the New York Times) barely mention the stage show at all. If Sinatra was looking to rejuvenate his career - to get his mojo back - by returning to the scene of his triumphs from the Dorsey days onwards, it wasn’t happening. Or was it?

# # #

By the grace of God, a French radio outfit broadcast 20 minutes of one of the Paramount Theater stage shows and a recording of that broadcast survives. That in itself is both significant and unusual. Ever since roughly WW1, when feature-length motion pictures began to overtake live vaudeville, there had been a business model of presenting entertainers - singers, dancers, comics, magicians, jugglers, and what have you - at major movie houses in the bigger cities across the country. As a venue or platform, as we would say today, shows in cinemas were a direct extension of vaudeville. Dance bands in particular, even before the start of the swing era, were extremely popular in theaters; the closest that most musicians came to playing concerts, as we understand the term today, ie, performances where the audience was supposed to sit down rather than dance, was between features at midtown cinemas.

The movie theater circuit was the lifeblood of the band business and popular music in general: every major band and singer did them, including Sinatra as late as 1956 and Nat King Cole with Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie in 1957 (both at the Paramount). And yet, we have little idea what these shows were like. There are virtually no actual recordings of movie theater stage shows, although perhaps we can infer that they must be a lot like the musical short subjects of the 1930s and ‘40s, the Vitaphones and others, as well as the early TV variety shows of the 1950s. (There’s also the secondary evidence of reviews in Variety or occasionally the more mainstream news outlets, and by columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan.) But still, virtually all radio broadcasts emanated from either ballrooms or network studios, and no one seems to have ever gone into the Paramount with a tape or even a wire recorder.

So this French broadcast is a very big deal; the announcer mentions the program is called Broadway Melody (Broadway Melodie). (One source indicates that this was part of the Voice of America network - “La voix de l’Amérique” - but I have been unable to confirm that.) I’m especially grateful to my pal, Chuck Granata, who was among the first Sinatraphiles to even know about its existence. Chuck had planned to include these 1951 tracks as part of a two-CD compilation titled Live Performances: The Columbia Years, 1943-1951. (This was set to be released by Sony-BMG Legacy in 2018, but Sinatra Enterprises pulled the plug on it at the last minute. Their loss!) Chuck remastered the Paramount tracks, and they sound better than ever on his compilation - I’m grateful to him for allowing me to include them here.

Lastly: It’s always a chuckle to hear foreign announcers introducing American songs: there’s a Spanish broadcast from the Astor Roof from 1940 by Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra, in which we hear the deep-voiced Spanish announcer introduce one of Sinatra’s tunes as “Noché Profundo!” (“Deep Night”) Here, the announcer sounds very Inspector Clouseau when he calls the tune as “When You Are Smiling.” (Apparently contractions are too much for them to deal with.) He announces the second vocal as “If I had a chance to love you,” which suggests that the concert was pre- taped and then broadcast over French radio, since he obviously took the title from Sinatra’s slight mangling of the actual title, “Would I Love You.”

Broadway Melody: Show opening (including “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” instrumental, Joe Bushkin, playing piano and conducting the house orchestra)

There are a lot of announcements in French throughout, starting with the opening of the radio series Broadway Melody (no apparent connection with the movie musical film series). We hear a lot of hub-hub, but through it all, a very boisterous, energetic orchestra, being agreeably directed by the pianist Joe Bushkin. If the band sounds great here, there’s a reason. As Bushkin told Chuck and myself in 1992, “When we were at the Paramount, [we used] the same guys who did his Bulova show that week.” In other words, it wasn’t the usual theater house orchestra, but the top players who were with Sinatra on his CBS show and probably his Columbia recordings as well.

Bushkin vividly remembered conducting on this gig, though partly for another reason: in addition to playing multiple shows all day long at the Paramount, he was also working, at the same time, with his trio at the Embers on East 54th Street, run by Swing Street veteran Ralph Watkins. “I did both jobs for two weeks. It almost killed me. I played until four in the morning, you had to be there at 11:30PM. It knocked me out. And Ralph Watkins was so good. He said, ‘Jesus, we're trying to get Erroll Garner…’ or somebody... Eddie Heywood... They were booked. He said, ‘I'm getting heat from my partners. You've got to do the two weeks anyway.’ Well, he said, ‘Don't worry about getting here. Whenever the show's over... Take your time…’ And then I was off, because Erroll Garner was going in after the two weeks. It killed me.”

Whoever is in the band, they sound like they’re accustomed to playing together and are sufficiently motivated and fired up by Sinatra and Bushkin, two expert leaders who knew how to get the most from an orchestra. The drummer is very noteworthy as well; Sinatra’s usual percussionist in this period was Johnny Blowers, but there’s no way of knowing whether it’s him or not playing here.

Part one of three. Apologies that I was only able to get the first of the eight tracks on this first post - expect the others tomorrow (Wednesday December 13) and Thursday (December 14).

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here.

December 1: The Early Years 1935-42 hosted by Will Friedwald

December 4: The Columbia Years 1943-’49 hosted by Ken Poston

December 5: The Radio Years: hosted by Chuck Granata

December 6: The Fall and Rise (1950-’54) hosted by Will Friedwald

December 7: Frank and Nelson hosted by Will Friedwald

December 8: The Capitol Years hosted by Loren Schoenberg

December 9: Bonus! Sing! Sing! Sing! Some Frank Conversation with Adam Gopnik

December 11: The Movies: Hosted by Chuck Granata

December 12: The Early Reprise Years 1960-'65 hosted by Loren Schoenberg

December 13:The Concert Years hosted by Ken Poston

December 14: The Rat Pack hosted by Ken Poston

December 15: Inside the Studio hosted by Chuck Granata

December 16: Bonus! In the Wee Small Hours with AJ Lambert (Sinatra’s granddaughter)

December 18: 1965-1974 The Main Event hosted by Will Friedwald

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

Happy Birthday, Mr. Chairman.

Very insightful article, thanks.