Revising Ella, Part 2: “Judy, My Judy”

continued from yesterday…

There’s one more point in the Apollo story that’s worthy of discussion: Ella Fitzgerald consistently said that at that legendary amateur contest, she had originally planned to compete as a dancer, but she didn’t want to follow the Edwards Sisters, so she made a last minute decision to sing instead. There is actually a brief film of the Edwards Sisters, with Duke Ellington’s Orchestra in 1949, which corroborates that part of the story; yes, they were clearly a hard act to follow.

Fitzgerald’s much-repeated version of this oft-told tale is in the Revisionist History episode, in the form of excerpts from an interview with Ella by Andre Previn in 1979. Fitzgerald always said that when she spontaneously decided to sing, she imitated a record her mother loved by Connie Boswell, the great jazz and pop vocalist and radio star from New Orleans, which had the song “Judy” on one side and “The Object of My Affection” on the other. As she told Previn:

"My mother had a record of Miss Connie Boswell, who I think was one of the greatest singers that ever lived. And she used to play ‘The Object of My Affection’ and ‘Judy.’ And I got so I used to sing it. And I tried to sing ‘Judy.’” She sings a few lines of the 1934 song by Hoagy Carmichael and Sammy Lerner. Then, she tells Previn, “I sang ‘Judy’ and the audience applauded so much I sang ‘Object of My Affection.’ That was the other side of the record. And I won first prize." ($25.00)

Connie Boswell did sing Pinky Tomlin’s “The Object of My Affection,” though not as a solo, but as a member of the Boswell Sisters, the highly innovative vocal trio that reigned as one of the most popular acts of the 1930s. That record wasn’t actually made until December 1934, a month or so after the Apollo Theater contest. However, the Boswells could well have been singing it on the radio prior to the contest; and there’s enough of Connie singing solo (including the first half chorus) for it to be understandable that Fitzgerald remembered it as a Connie Boswell record rather than a Boswell Sisters record.

What Fitzgerald describes as “the flip side” is more problematic. Connie Boswell never made a record of “Judy,” in 1934 or any other year. What’s more, David McCain, the Boswell of the Boswell Sisters, has vigorously researched every gig, every clipping, and every documented radio appearance by the Boswells, and there’s no evidence at all that Connie Boswell ever sang “Judy.” Ella Fitzgerald is the only one who ever mentioned it.

According to Hoagy Carmichael’s biographer, the late Dick Sudhalter, “Judy” originated as “something Hoagy had devised in 1928, a jam tune based on an unconventional descending chord pattern. Hoagy called it ‘Judy’—though [the composer’s friend] Wad Allen, tickled by its ‘weird’ chord movement, had nicknamed it “Birdseed.’” Carmichael would record it at least three times: first as an instrumental in October, 1933, a track that still has not been issued. (It’s listed as having a vocal by Carmichael, but Sudhalter describes it as an instrumental.)

In March 1934, Carmichael recorded it for Victor with his own vocal, a master that was issued with only his name as composer, and with a very different set of words. This original text begins, “She’s the one for me / Heaven sent her to be / Judy, my Judy.” This was apparently the composer’s own lyric, but the publisher wasn’t satisfied, and subsequently commissioned a new text from Sammy Lerner. This is the one that we know, which starts, “If a voice can bring / The hope of the Spring, / that’s Judy, my Judy.” Both lyrics conclude with the line, “That’s Judy, sure as you’re born,” although the Lerner lyric is at least a bit more consistently poetic.

The new lyric was apparently first recorded in England, over the summer of 1934, by London bandleaders Carroll Gibbons, Billy Cotton, and Lew Stone, the latter with the formidable Nat Gonella, England’s answer to Louis Armstrong, singing and playing trumpet. There’s also an especially lovely reading by the outstanding singer Al Bowlly, accompanying himself on guitar and with Monia Liter’s piano. Back in the USA, it was picked up by the Dorsey Brothers, in April as an instrumental with a stylish Glenn Miller arrangement, and the Casa Loma Orchestra, featuring trombonist Pee Wee Hunt, singing in a Hoagy-ish drawl. In 1939, Bob Chester’s Orchestra did a modern swing version, and Carmichael himself recorded the song for the third time - now with the Lerner lyric - for Decca, in 1942.

“Judy” is the only song by the team of Hoagy Carmichael and Sammy Lerner. Lerner (1903-1989) is the kind of songwriter who routinely gets confused with other songwriters, since there were so many from the period named “Sammy”: Fain, Cahn, and Timberg, to name a few. Around the same time Lerner wrote “Judy,” he was also doing lyrics for Fleischer Brothers cartoons released by Paramount Pictures, a job he shared with composer Sammy Timberg. In 1934, the same year that “Judy” was published, Lerner wrote the words and music for the theme song of the “Popeye” cartoons, which hopefully supplied him with an annuity that he could live on for the rest of his long life.

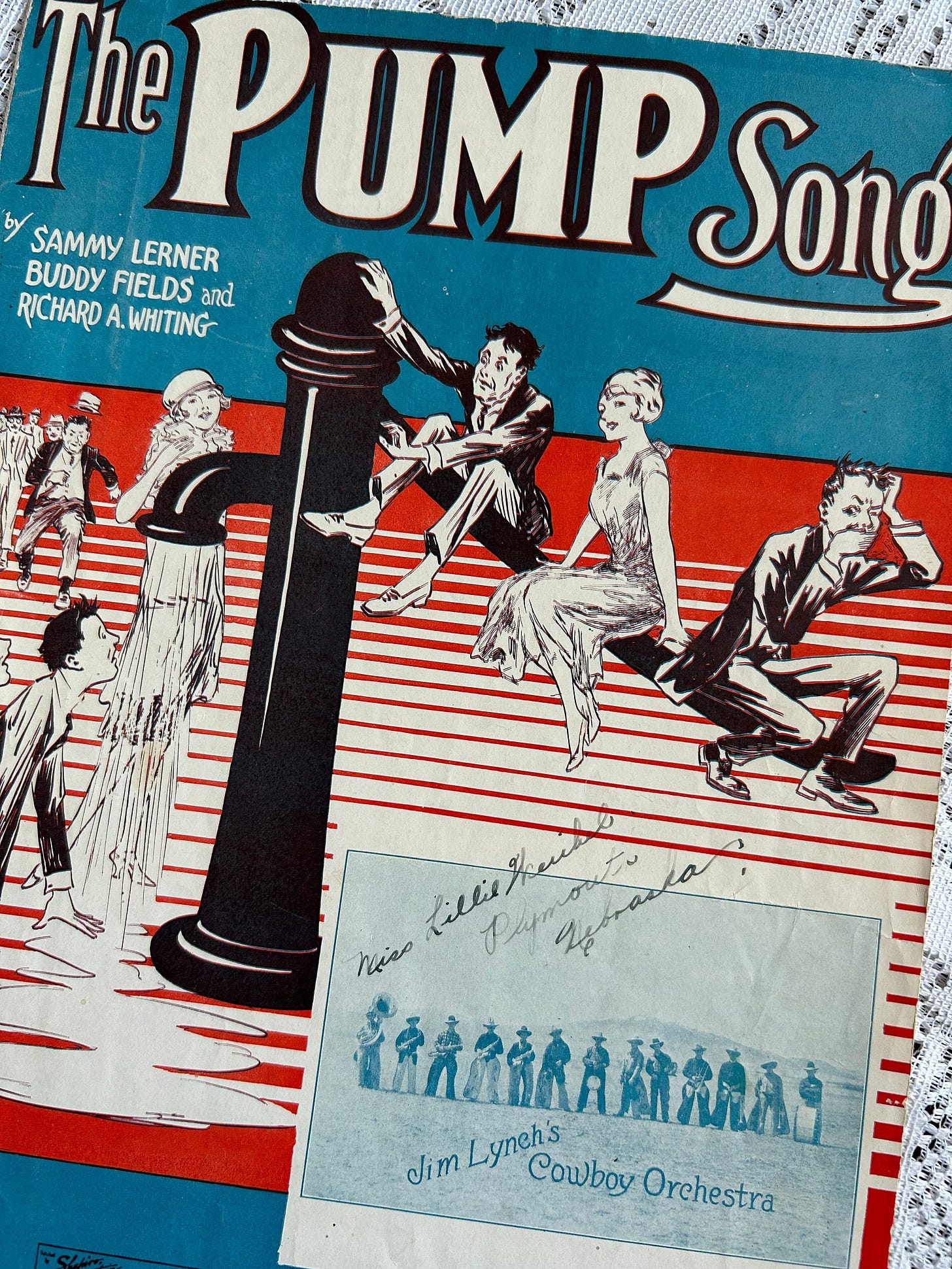

One further point that distinguished Lerner from the other Sammys was that he was much more international in his purview. He was born in Roumania, grew up in Detroit, and was publishing songs by the age of 23. Some of his first numbers were collaborations in Chicago with Richard Whiting, including a zingy double-entendre novelty called “The Pump Song,” and then with Dana Suesse and Burton Lane. In the mid and late ‘30s, Lerner was also actively writing songs for English musicals, both on stage and screen (including the 1937 Gangway, starring Jessie Matthews), which meant that he was spending a lot of his time in Europe. His biggest standard is probably the English lyrics to Friedrich Hollaender’s German classic for Marlene Dietrich, “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt” which he retitled “Falling in Love Again.”

Lerner wrote a handful of songs popular in the early swing era, like “Is It True What They Say About Dixie” (1936) which was later annexed by Al Jolson and included in Jolson Sings Again (1949). And yes, the way Larry Parks mimes it and Jolson sings it (especially in his classic collaboration with The Mills Brothers), there’s no doubt that “it” is indeed true. Both “Dixie” and “(Oh Suzanna) Dust Off that Old Pianna” (1935) were written with Gerald Marks, and the latter is well-remembered by jazz fans for the classic recording by Fats Waller and his Rhythm. “Everybody’s Laughing,” was immortalized in the stunning 1938 interpretation by Teddy Wilson and his Orchestra, starring Billie Holiday and Lester Young, with a brief trumpet break by Harry James. (There also were sticky-sweet period versions by Ted Fio Rito and his Orchestra as well as Shep Fields and his Rippling Rhythm.) “Breakfast in Harlem '' was written for the British film Transatlantic Rhythm (1936) and likewise rendered beautifully by the essential team of Buck and Bubbles.

Sammy Lerner kept writing through the war, but gradually retired by the early 1950s. All those “Popeye” royalties certainly escalated during the television era.

One of many revelations in Judith Tick’s biography is that Fitzgerald gave a lot more interviews over the years than most of us have realized, although few of them can be considered substantial. Because she tells the story of the Apollo amateur night - her version at least - so many times, it turns out that she probably mentions “Judy” more than any other song, with the possible exception of “A-Tisket, A-Tasket.” Which makes it all the more surprising that Ella never came back to it - she never recorded it, and there’s no live version or even a mention of a performance in an unrecorded concert.

Yet plenty of people did record “Judy,” which became at least a minor jazz standard. Instrumental virtuosos Art Tatum and Lionel Hampton both addressed it before the 1930s were over, as did Oscar Peterson, who probably learned it from Tatum, on his 1963 album with Nelson Riddle. Louis Prima recorded it with his big band on RCA circa 1949 and then again in two distinct takes in 1958 with his Las Vegas ensemble, including Keely Smith, Sam Butera and the Witnesses.

The other point about “Judy” is that the song also is said to have inspired the 12-year-old Frances Ethel Gumm to change her name to Judy Garland. (Needless to say, following in the tradition of Boswell and Fitzgerald, Garland also never recorded it.) This makes Tony Bennett’s lovely, slow version, with the Ralph Sharon Trio on their great 1964 album, When Lights are Low, all the more poignant, since Tony is the rare individual who was very close to both Ella Fitzgerald and Judy Garland.

What other song inspired the careers of two all time legends of American music? And what other lyricist put the most famous words ever in the mouths of both Marlena Dietrich and Popeye the Sailor? Still, Sammy Lerner and his role in all of this remains the source of much confusion. To this day, when you google his name, the first image that comes up is a picture of Sammy Cahn.

The episode of Revisionist History discussed above can be heard here.

One other aggressive Fleischer cartoon fan compiled this youtube playlist of Sammy Lerner songs - which also includes James F. Hanley’s “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart.” (as a sort of bonus track, one imagines.)

Lastly, My buddy, blogger and latter day vaudevillian Trav S. D. has also written an appreciation of Sammy Lerner, and you can access it here.