Very Special Thanks to Nick Rossi for his input here, as you will see, as well as Jordan Taylor, Dave Weiner, and, as always, Elizabeth Zimmer! (PS the key identifications, which are all concert keys, are courtesy Nick.)

Quick Question: What was Nat King Cole’s first major hit? Most of the interviews he gave would lead you to think “Sweet Lorraine” was the first time anybody ever paid attention to him, especially as a singer. More properly, “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” from his first session at Capitol Records, was the record that really helped him attain a whole new level - and the one that Capitol, in its subsequent PR, liked to acknowledge as his breakthrough hit.

But the first disc of Nat King Cole that really placed high on a chart of some kind was “That Ain’t Right.” This was a very basic - and very funny - 12-bar blues that he had written sometime in 1941. As far as we know, this was the first song he would sell to Mills. As I observe in my biography of Cole, Mills was a devil who delivered - at least he did something to help Cole’s career and to push those songs he published; he was a tireless promoter of the songs in his catalog. In fact, Mills did everything for those songs - except actually write them. (At least, this is what we believe to be true by the early ‘40s when he worked with Cole; Mills biographer Don McGlynn feels that there was a period early on when Mills did have some creative input into the lyrics and music.) In any case, Mills bought both “That Ain’t Right” and “Straighten Up and Fly Right” outright from Cole, lock, stock, and barrel, with no future royalties and with Mills putting himself down as co-author. (Which explains why, after he became famous, Cole avoided both those songs as much as he could - although he remade “Straighten Up” twice, he rarely played it on personal appearances or broadcasts.)

The original King Cole Trio - with guitarist Oscar Moore and bassist Wesley Prince - recorded “That Ain’t Right” (in Bb) in New York in October 1941, at the last of their four sessions for Decca Records. J. Mayo Williams probably supervised the date, but Milt Gabler was also possibly involved.

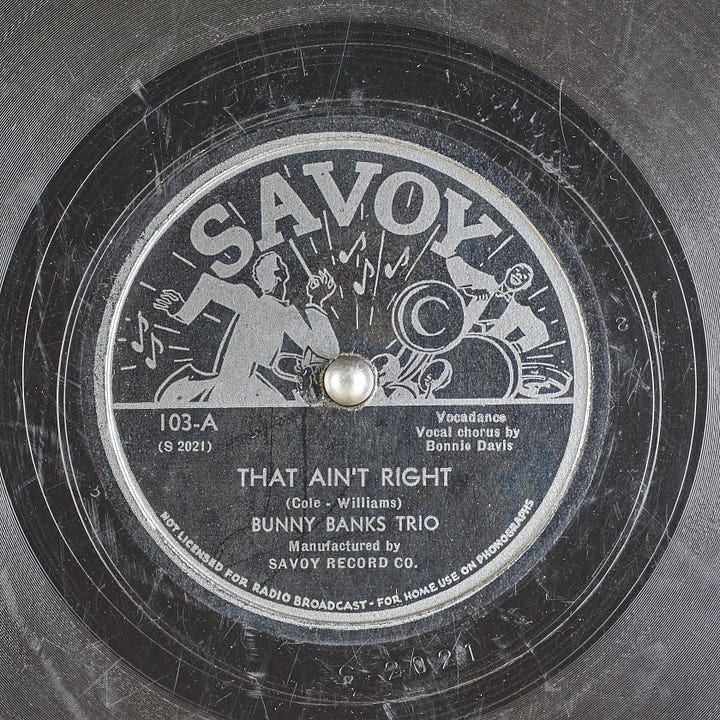

Cole was 22 at the time of the recording; in subsequent years, he would grow considerably as both a jazz pianist and a ballad singer, but he already is quite formidable as a blues artist, both playing and singing. Here’s the original Decca record, issued around July 1942. (Most of the earlier Cole releases for Decca were first issued on their “Sepia Series,” but here they are on the regular mainstream Decca label. PS: In 1947, at the height of the Trio’s fame during the Capitol years, Decca reissued “That Ain’t Right” - illustrated above - b/w a different jive number, “Scotchin’ with the Soda.” Both Decca reissues credit Cole as sole author, but most other releases give co-credit to Mills.)

Guitarist and historian Nick Rossi has this to tell us about “That Ain’t Right”:

”In terms of performance, I feel compelled to sing the praises of both Cole and Moore. Each demonstrate a fantastic and highly personal approach to playing the blues here. The KC3 is often presented in contrast with the (later) Three Blazers led by Moore’s older brother Johnny. Typically, the Blazers are praised for their grittier approach, while Cole and Co. are portrayed as slick and sophisticated. On ‘That Ain’t Right,’ it’s evident that the blues and playing the blues was very much part of the King Cole Trio vocabulary and they did so in a very creative way. In this regard, Moore in particular has a very unique style different from his brother’s, but no less compelling. Considering how big this record was and for how long it remained on the Harlem Hit Parade, one is forced to reconsider how much of an impact the record as well as the playing of Oscar Moore (and Nat!) may have had on the developing Rhythm & Blues world, which was just coming into focus during this period. Also important is that Moore is on electric guitar here, and instrument he had been using since spring 1940 sometime after seeing/hearing Charlie Christian. In 1942, the electric guitar was still something of a novelty, although Oscar has full command of the instrument. It’s only after the ban and particularly after World War Two that it became ubiquitous in both jazz and R&B.”

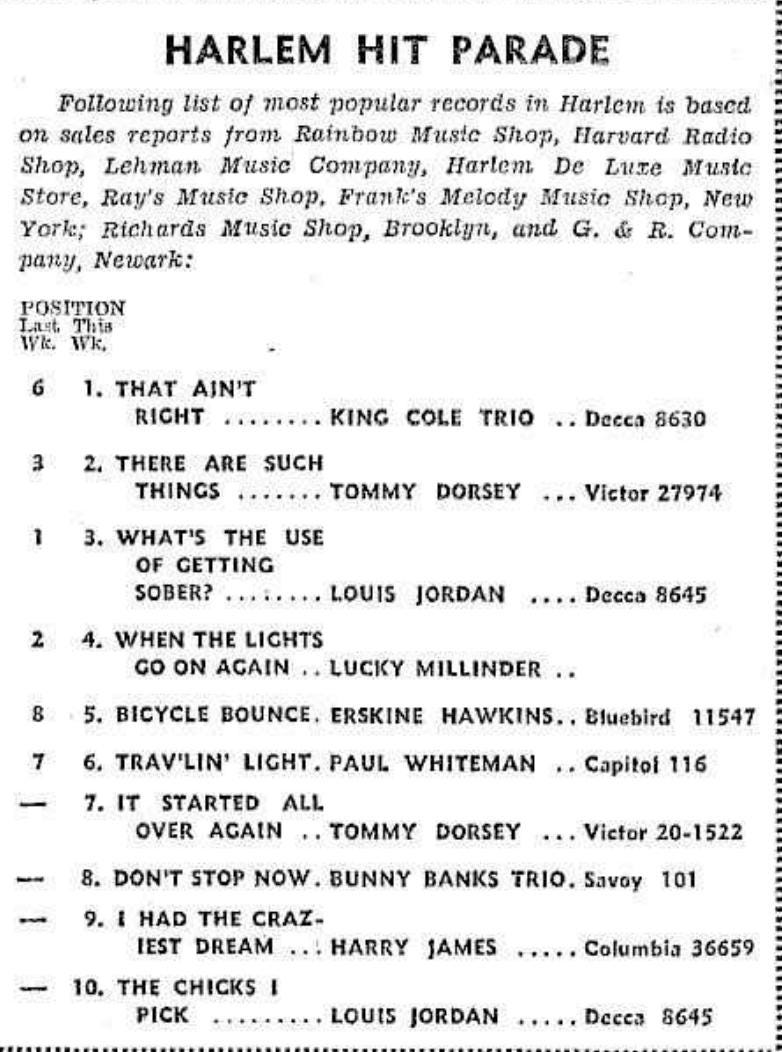

“That Ain’t Right” was a very big deal for Nat in 1942; it was the first song or record of his to chart, attaining the number one spot on the “Harlem Hit Parade,” Billboard’s original title for the R&B chart. The track was released in Summer 1942 and showed up on the chart at the end of the year, by which point the country was engulfed in the infamous record ban of 1942-’44, and Cole couldn’t have released a follow-up disc even if had then been under contract to a label - which he wasn’t.

(Below, from Billboard, January 30, 1943. The Trio shares the best-seller list in the “race” market along with Louis Jordan, Tommy Dorsey & Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday singing pseudonymically with Paul Whiteman, and even “The Bunny Banks Trio,” an early KC3 knockoff style group.)

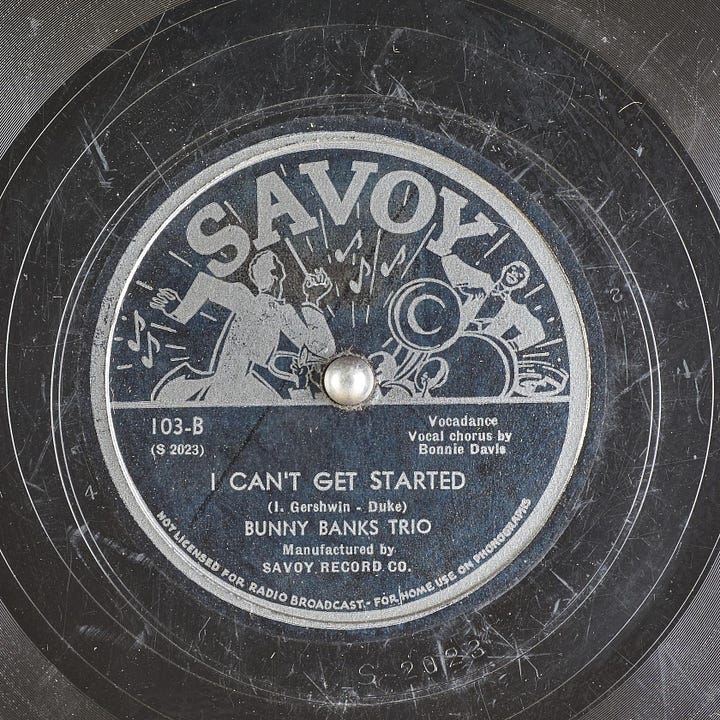

When “That Ain’t Right” was charting, Savoy Records recorded and released the first so-called “cover” of the song, by a King Cole Trio-style ensemble billed as “The Bunny Banks Trio,” featuring pianist Clem Moorman, guitarist Ernie Ransome, and bassist Henry Padgette backing singer Gertrude Melba Smith billed as “Bonnie Davis.” This was cut for Savoy in New York during the summer of 1942 (in F), presumably before the AFM ban went into effect, but who knows? (Nick Rossi reminds us that Marv Goldberg has written a fine history of Moorman and his groups here.)

Like I say, Irving Mills earned his money. For years he had been advocating for a major Hollywood studio to produce an all-Black movie musical based on his song catalog. In 1943, he got his wish when 20th Century Fox released Stormy Weather. The bulk of the score was by the major heavyweight veteran songwriters who had worked with Mills Music in the firm’s glory years—Jimmy McHugh & Dorothy Fields, Harold Arlen & Ted Koehler, Cab Calloway, Fats Waller & Andy Razaf—the majority of whom had either written for or performed at The Cotton Club.

Mills also arranged for a newcomer to be included in the score - that song he had purchased from Nat Cole - “That Ain’t Right” (here in C). For many, the Fats Waller sequence, which he shares with the veteran blues singer and actress Ada Brown, is, no less than the Nicholas Brothers or Bill Robinson, one of the highlights of the movie. Both the humor and the passion of the blues are given in abundance here, in a way never seen elsewhere in a Hollywood musical. Cole’s original song also provides the platform for a symbolic passing of the torch, from the great pianist-singer of one generation, Thomas Wright Waller, to that of the next, Nathaniel Adams Coles. (One other thing they had in common was that both led tragically short lives.) Famously, Waller also performs what might be the definitive version of his own best-known work, the jazz standard “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” It’s a powerful and immensely entertaining, self -contained sequence - less than four minutes long - a great jazz short subject (anticipating Jammin’ the Blues from the following year) unto itself. (As Nick also points out, future King Cole Trio guitarist Irving Ashby is playing for Fats here.)

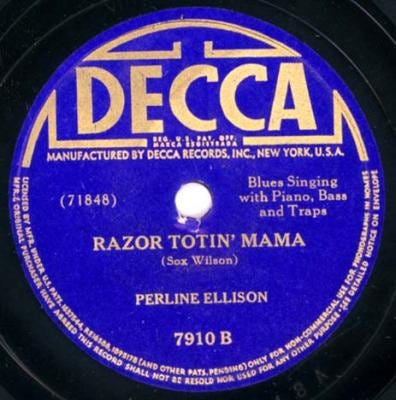

In 1944, a lesser-known blues singer named Perline Ellison recorded a “sequel” song, which was a fairly common idea in the commercial blues market: to take the basic melody of a familiar, successful blues number and simply add more verses to it. (For years, whenever you would ask my late father what his favorite song was, he would always say, “New Rubbin’ on the Darn Old Thing” by Oscar’s Chicago Swingers.)

“New That Ain’t Right” was recorded for Decca in New York, March 9, 1944 (in Eb), with house pianist Sam Price, bassist Abe Bolar, and drummer Doc West. This was apparently produced by J. Mayo Williams, who had also produced most of Cole’s own Decca sessions. Williams apparently takes credit for composing the song as well; by 1944 Nat wasn’t thinking about this song any more, since, like “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” he wasn’t making any money from it regardless. (Unrelated fact worth mentioning: Perline is a rather unusual name, but, coincidentally, Nat Cole’s mother was named Perlina.)

The next great thing to happen to Cole’s song was in 1947, when the legendary Mildred Bailey recorded it twice, once for Victor, the second as a live aircheck that was subsequently released by V-Disc (in the unlikely key of B natural). Here she’s backed up by a King Cole Trio-style group of the equally-legendary pianist Ellis Larkins, guitarist Gene Fields and bassist Beverly Peer (earlier with Chick Webb and later with Bobby Short). In the best tradition, Mildred adds some of her own lyrics, in the “floating” blues style. Here’s the live version, prefaced by banter with DJ and personality Art Ford.

One last version - or two: Frankie Laine - a longtime friend and fan of Nat King Cole - recorded the song as one of his first Mercury singles, released in 1948, His treatment starts with the opening lines of another popular blues, Billy Eckstine’s “Jelly, Jelly,” and then goes into Cole’s song; he titles it “Baby That Ain’t Right” (and brings it back to the original Bb) and the label gives credit to Mills and Cole. (Nick believes it’s Tony Mottola on guitar - would that I had thought to ask him!)

Laine remade “That Ain’t Right Baby” years later on a Columbia album in stereo. He also sang it on his television debut, on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town, January 8, 1950. Note that at the end of the song, he catches the “Mule Train” home!

One final thought from Nick, regarding the guitarists on all these different versions of the song: “Each demonstrate an approach to small band playing that was pioneered by Oscar Moore with the King Cole Trio. So even if each were not directly influenced by Oscar in terms of technique or vocabulary, it can be argued that if it were not for Moore and the early successes of the King Cole Trio on radio, jukeboxes, and in person, the character of all of these recordings would be quite different. “

The website “Lyricfind” gives the following lyrics, and credits one Paul John Weller (?) as “songwriter” :

Baby, baby, what is the matter with you?

Baby, baby, what is the matter with you?

You got the world in a jug

And you don't have a thing to do

I always told you, baby

You'll be the death of me

'cause when I'm always with you

I get the third degree

That ain't right

Baby, that ain't right at all

Takin' all my money

Goin' out, havin' yourself a ball

I took you to a night club

And bought you pink champagne

You rolled home in a taxi

And I caught the subway train

That ain't right

Baby, that ain't right at all

Takin' all my money

Goin' out, havin' yourself a ball

I went to a fortune teller

And had my fortune told

He said you didn't love me

All you wanted was my gold

That ain't right

Baby, that ain't right at all

Takin' all my money

Goin' out, havin' yourself a ball

coming next:

The Dinah Washington Centennial -

A Complete Annotated Filmography

Part One:

The “Showtime at the Apollo” Films (1954)

Part Two:

Bandstand Revue (1955)

Crescendo (1957)

Part Three:

Jazz on a Summer’s Day (filmed 1957, released 1958)

Part Four

CBC (1959)

The Singin’, Swingin’ Years (1959)

Very Special thanks to the fabulous Ms. Elizabeth Zimmer, for expert proofreading of this page, and scanning for typos, mistakes, and other assorted boo-boos!

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com; click here.

SING! SING! SING!

August 17 - “Fat Daddies & Skinny Mamas: The Body Positive Show”

August 24 - “The Dinah Washington Centennial: Back to the Blues”

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

Seems to be an influence either on or from "I've Got News for You" as sung by Woody Herman and Ray Charles but I haven't been able to find out when that song was written. (Or is this a common blues I haven't heard elsewhere?)

Considering that That Ain't Right was recorded in October 1941, it's highly unlikely that Milt Gabler had any involvement--he told me he was hired by Decca in December 1941.