"I Happen to Like New York"

A Truly Subversive Song: "And when the undertaker starts to ring my funeral bell..." (A Bobby Short and belated Judy Garland Centennial Story)

This being the Bobby Short centennial, I have heard “I Happen to Like New York” many times this past season. It’s a remarkable song - lyrically, it’s absolutely archetypical and quintessential Cole Porter, but musically it’s something else again.

The Backstory:

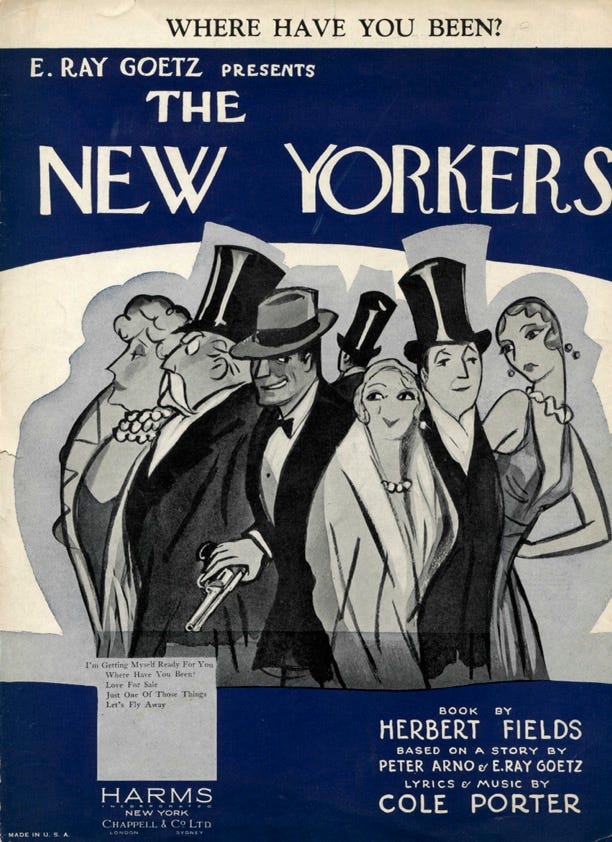

Cole Porter wrote “I Happen to Like New York” for a 1930 Broadway show - a book show, mind you, not a revue - called The New Yorkers - produced by E. Ray Goetz (1886-1954), a veteran songwriter and producer who had briefly been Irving Berlin’s brother-in-law. In some ways, we can describe this production as Porter’s first “real New York” show. To show you what I mean, here’s a rough chronology of Porter’s works in the 1920s:

Hitchy Koo of 1922 (closed in Philadelphia)

Greenwich Village Follies (1922) (Atlantic City) This show did make it to New York, but by the time it did, most of Porter’s songs were no longer in the score.

La Revue des Ambassadeurs (1928) (Paris)

Paris (1928) A Broadway show which takes place in Paris

Wake Up and Dream (1929) A London revue which also briefly played New York

Fifty Million Frenchmen (1929) Another Broadway show which takes place in Paris

The Battle of Paris (1929) An early Hollywood movie musical - for which Porter wrote the great song, “They All Fall in Love” - and which is also set in Paris.

See what I mean? Porter wrote shows that were produced in Paris and London, and, at the same time, all of his early shows written for Broadway were, perhaps coincidentally, invariably set in Paris. In this period, Porter was the original “American Boy in Paris.”

Thus, The New Yorkers should be considered Porter’s first “real New York” musical - made by and for New Yorkers and with a distinct New York sensibility. In fact, when The New Yorkers opened at B. S. Moss’s Broadway Theater on December 8, 1930, there was already one completely different but equally great New York song in the score: “Take Me Back to Manhattan.” (Here’s Bobby again.)

According to the ever-reliable Robert Kimball, Porter composed “I Happen to Like New York” after the show had opened and inserted it into the score in about a month into the run. Porter was apparently in the middle of the ocean when he composed it - which might have inspired the lines, “I like to go to Battery Park / And watch those liners booming in.” Kimball quotes a notice from The New York Evening Journal (December 23, 1930) which informs us that Porter was sailing to Monte Carlo for a vacation, even as “the whole town (New York) is whistling and singing the big hit songs from The New Yorkers.” The paper informs us that Porter had written a new song while at sea which he transmitted to Ray Goetz via wireless. (I am not sure how that worked in terms of sending music.) “I Happen to Like New York” apparently was heard in The New Yorkers beginning during the week of January 19, 1931, and it was sung by Oscar Ragland.

As we know, at this time, every Broadway show had at least a dozen or more songs; there were virtually no original cast albums, and only a handful of songs from every show made it onto a recording at the time. At least four of the songs from The New Yorkers were recorded by singers and dance bands in the period:

“Love for Sale” (which was quickly banned by the BBC and not heard much on USA radio either)

“Let’s Fly Away”

“I’m Getting Myself Ready for You”

”Where Have You Been?”

Note that the score also included a song titled “Just One of Those Things,” which was not the same mega-standard that Porter wrote for Jubilee five years later; this “Just One of Those Things,” had completely different words and music and was dropped in Philadelphia.

But, disappointingly, both “Take Me Back to Manhattan” and “I Happen to Like New York” would not be recorded for many years to come. Stay tuned.

The music:

It could just be that the song was too unusual, musically, and perhaps too risque, lyrically, to be considered a candidate for mass-market representation via commercial recordings or radio. Once a few years ago, Vince Giordano was asked to play it with his band, the Nighthawks; he hadn’t been familiar with the song beforehand, and was highly surprised - it sounded nothing like any other Cole Porter song he had ever played, and he’s played them all.

The most conventional aspect of “I Happen to Like New York” is that it is in roughly what could be considered standard AABA form, except that the first two A sections are 12 measures, then the B bridge is eight measures, and the final A is really A prime (A’) in that it has an additional four-bar tag. So, in all, we have a rather unusual total of 48 measures.

I asked our friend Dan Weinstein, Los Angeles-based violinist and trombonist, for his take on it. After listening to the two most famous recordings, Judy Garland and Bobby Short, he offered thus:

Bobby Short and Judy Garland are as different as two recordings of the same tune can be. The harmonic structure is a bit static, or a better word might be suspended. The 3/2 time with the same "pedal point" bass note on the second beat under the back and forth chords builds intensity. The bridge uses the same approach in another key, then back to the first tonality to wrap it up. It's a little "inside" to compare with Schoenberg, but the experiments of early 20th century "classical" composers would open the door for popular composers such as Porter to use different approaches, such as this. I'd say it all underpins the lyrics well, in that the build up of intensity matches the increasing need to justify the lyricist's point of view. Amazingly, this is kind of a "list" song, but utterly unlike any of Porter's more light-hearted entries in that genre.

Possibly the words "stink" and "hell" kept mainstream bandleaders like Leo Reisman from making a record of it. Re-listening to Bobby Short, I realized that the "bass on 2" approach was in the Garland arrangement, not Bobby's. The "tinkling" you mention is him playing his chords in the higher part of the piano, thus giving it a bell-like effect. When he moves the same chords down an octave, it gives the harmony more weight.

After Michael Lavine shared with us a copy of the 1931 sheet music, Dan added:

The first thing I noticed is that the "pedal point" or ostinato bass (meaning the same, unchanging bass note under shifting chords) is a major harmonic component of the song, and was faithfully performed by Bobby Short and Judy Garland's accompanying orchestra and chorus.) This may be unprecedented in "popular" songs of the period, though I wouldn't swear to that. I'll hack my way through this and get back to you if I have any other observations.

Then, there the time signature, also known as meter: 3/2 would be extremely rare in a popular music song sheet of any period. 3/4 is common for waltzes, of course, but 3/2 not at all. The pattern of two measures of 3/2 with the bass notes hitting on 1 and 3 of the first measure and 2 of the second measure is likewise almost unheard of in pop music. On to the chords used. This is not Gershwin's New York City sound by a long stretch. I'd describe the harmonies and their voicings as being somewhat desolate sounding, echoing the irony of the lyrics. Bobby Short's version comes close to the song sheet but the Judy Garland extravaganza seems to attempt to sweeten everything way beyond Porter's intention. However, Judy's dramatic reading of the lyrics fits the ambivalence of the meaning to a "T"!

The lyrics:

First, there is no verse, except that on the studio recording (not the live TV performance) by Judy Garland, she sings a special material verse that I can only imagine was written for her by longtime rabbi Roger Edens. (Note that this verse is not heard in Garland’s famous 1963 CBS TV performance of the song.)

Choir:

Judy, it’s nice to have you here.

New York’s brighter when you are near.Judy:

Everytime I go away, off the beaten track,

I live only for the day when I know I’m back

Cole Porter didn’t write that! The song proper starts here:

I happen to like New York, I happen to love this town.

I like the city air, I like to drink of it

The more I see New York, the more I think of it

I like the sight and the sound and even the stink of it

I happen to like New York

Porter was almost 40, but this was still early in his career. Here, he’s establishing if not an entirely new genre of songwriting, certainly a unique subset of songs which both praise and affectionately gripe about a certain subject matter - and it’s especially effective when that topic is the city of New York. Other Porter songs about New York derive from the same idea - glorifying New York and complaining about it at the same time, like “Take Me Back to Manhattan,” wherein the line, “that dear old dirty town” pretty much says it all, “Don’t Monkey With Broadway” and “When Love Beckoned (On 52nd St).” Among other songwriters, Rodgers and Hart would capture this vibe precisely with “Give it Back to the Indians” and “Way Out West on West End Avenue” - much more so than on their earlier “Manhattan.”

Porter’s use of terms like “stink” and “later “hell” in the middle of this otherwise sincere-sounding, anthemic air is genuinely subversive; in a way, he reminds me of Thelonious Monk, who would seemingly randomly throw in chromaticisms and other discordant notes in the middle of a standard or an original ballad to deliberately undercut a mood. In 21st century parlance, Porter is being genuinely disruptive.

That Porter’s use of such devices was intended to ruffle feathers and upset apple carts is illustrated by the copy of the 1931 published sheet music that Michael Lavine shared with us. Whoever owned the music before Michael evidently thought that “stink” was too extreme, and therefore, crossed that word out, and wrote in “smell” instead. (Yes, he or she rewrote the rest of the line that that there would still be a rhyme there.)

I like to go to Battery Park and watch the liners booming in

I often ask myself why should it be

That they come so far across the sea?

I suppose it's because they all agree with me

They happen to like New York.

As we’ve seen, Porter was likely thinking about ocean liners coming “so far across the sea” because he was in the middle of the ocean, traveling on one at the very moment when he was composing “I Happen to Like New York.”

(I had my own Battery Park epiphany moment about 40 years ago, when I attended a sunrise Spring Solstice jazz concert at the very tip of lower Manhattan given by the combination of Don Cherry plus Sun Ra and his Arkestra. As the sun rose and the music crescendoed, we all became acutely aware that we were indeed entirely surrounded by “ocean liners booming in.”)

Last Sunday afternoon, I took a trip to Hackensack

But after I gave Hackensack the once over

I took the next train back.

I happen to like New York.

Like I say, this is quintessential Porter, writing a song about New York but also writing a song about making fun of the act of writing a song about New York at the same time. Really? The best thing he can say about New York is that it beats the heck out of Hackensack, New Jersey. Talk about damning with faint praise! (As Dan Weinstein has also observed, between the reference to “Hackensack” here and “Asbury Park” in “At Long Last Love,” it’s clear that Porter loved to utilize the entire state of New Jersey as a signifier for mediocrity.)

I happen to like New York, I happen to love this burg

And when I have to give the world my last farewell

And the undertaker comes to ring my funeral bell

I don't wanna go to heaven, don't wanna go to hell,

I happen to like New York,

I happen to like New York

I happen to like New York.

One of my favorite Porter quirks is his casual, ironic use of religion and spirituality in many texts: famously, there are the references to Genesis in both “Let’s Misbehave” and “They All Fall in Love,” as well as more the overtly irreverent religiosity in “Heaven Hop” and “Blow Gabriel Blow.” More about this shortly.

Lastly, when you do a google search on “I Happen to Like New York - Judy Garland - lyrics” you get a version of the text that does not include the Garland verse but does include these eight lines of non-Porter special material lyrics. These were never sung by Garland, but they were done by Liza Minnelli in her 1987 Carnegie Hall version and other performances:

And oh, the Easter Show at the Music Hall

A perfect delight

And oh, pastrami on rye at the Carnegie Deli

There's joy in each bite.And Madison Square for a Friday night fight

Or a walk along Broadway to gaze at the lights

And at Carnegie Hall where the atmosphere's right

Night after night after night.

The Recordings (Especially Judy & Bobby)

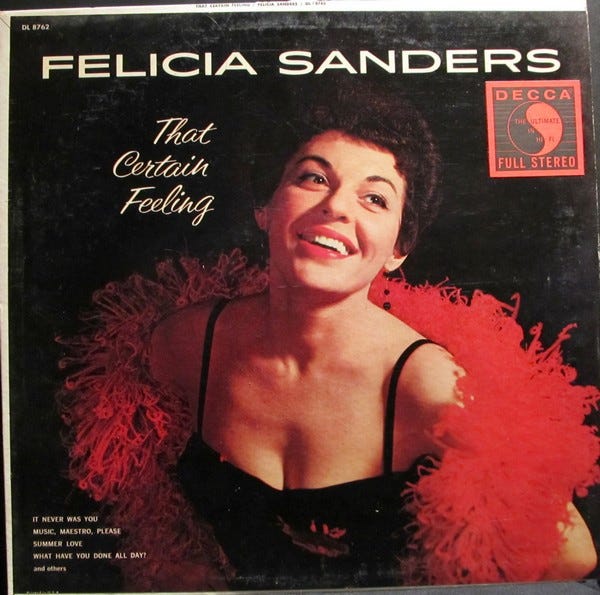

According to second hand songs, the premiere recording of this quintessential New York show tune was by the London-based vocalist Dorothy Carless in 1956. She was followed a year or so later by New York cabaret singer Felicia Sanders on her 1958 Decca LP That Certain Feeling.

And then we come to the classic version by Judy Garland - which is how most of us know it. Did Garland actually hear the Carless or Sanders recordings? More likely Roger Edens, who was in New York in 1930, saw The New Yorkers and remembered the song. In May 1959, Garland enjoyed a seven-night run at what was then the Metropolitan Opera House on 39th Street Broadway; it was the ideal time and place to introduce her version of a song virtually no one in the audience would have known. It was here, as far as we can determine, that she sang “I Happen to Like New York.” Gordon Jenkins, with whom she had collaborated on the classic Capitol Records album Alone, two years earlier, was her conductor and musical director, and he arranged the Porter song for her. (Thanks to Lawrence Schulman and Emily Coleman’s The Complete Judy Garland for this info.)

When she recorded it, a year later (August 1960) in London, with Norrie Paramour conducting, she used the Jenkins arrangement. (This studio version was released both on The London Sessions collection as well as the 1962 LP The Garland Touch.) As noted, the studio recording opens with a whole new “verse,” which was likely written for her by Edens, but it might have also been the work of Jenkins - it’s very similar to the words and music he wrote for his epic masterpiece Manhattan Tower - in fact, the whole megillah sounds like it could be a bonus track from the Manhattan Tower suite. (we’ll repeat it immediately below).

Choir:

Judy, it’s nice to have you here.Judy (spoken): Thank you.

Choir:

New York’s brighter when you are near.Judy:

Everytime I go away, off the beaten track,

I live only for the day when I know I’m back

It is, in fact, the combination of Garland and Jenkins that makes their “I Happen to Like New York” - and how they dig into Cole Porter’s harmonies, melodies, and lyrics - so amazingly special. Primarily, it’s that they double down on the spirituality; Jenkins overstuffs the chart with an angelic choir and all kinds of church music effects, making the whole thing sound like 19th century sacred music - Brahms, Mendelsohn, or Wagner. Even beyond the choir, the use of classical woodwinds as well as kettle drums make it clear that this is not your average Sinatra-era jazz-pop track; this is no song for swingin’ lovers.

The Garland-Jenkins “I Happen to Like New York” is nothing less than spectacular: it’s at once a rah-rah cheer praising Manhattan but also a spiritual anthem, a true “Come-to-Jesus” moment - while, at the same time, it’s an overt parody of both of those things.

Garland, Jenkins and the choir get even more over the top as we move into the bridge - the chorus gets louder and more aggressively, even violently angelic as Garland sings of her “trip to Hackensack” - the underscoring further enhances Porter’s irreverence and use of irony. The religious mood increases even as Garland sings of transitioning to the next world, but instead of revering Heaven, she resolutely dismisses both of the usual destinations of the afterlife and states plainly that even after the undertaker has rung her funeral bell, she wishes to remain in New York.

This isn’t just camp, this something beyond camp, this is something that so transcends camp that we might call it a kind of ubercamp.

In 1963, Garland performed “I Happen to Like New York” as part of Judy and her Guests, one of two CBS TV specials which preceded her 1963-1964 CBS series. This version may be even better: it’s only slightly toned down in its religious fervor - the original special material verse is not included, and the choir is omnipresent. Of course - it’s even better because we can actually see her.

A few more notable performances: the now-late Caterina Valente built a whole metrocentric album around the song in 1964, of which the title song was “I Happen to Like New York.” She’s the only other singer I have ever heard sing the Garland verse; in fact, she does a pretty accurate recreation of the Garland-Jenkins chart. (The full album is above.)

We’ve already included the Bobby Short recording once - from the 1974 album Live at the Café Carlyle - but it’s worth repeating. Short’s arrangement, which as Dan noted, has the singer pianist voicing Porter’s chords on the higher registers of the keyboard which gives the song a tinkling, chiming effect, making it even more classical and religious sounding.

Most performances from over the last 50 years use either the Garland or the Short version as a template. Caterina Valente clearly used Garland, as, not surprisingly, did Liza Minnelli. Clint Holmes recreated Bobby Short’s arrangement, using the piano like a choir of angels - this is the way Charles Turner performed it at Dizzy’s a few weeks ago in his centennial salute to Bobby Short, which brings us full circle, right back where we started from.

Special thanks to Elizabeth Zimmer, as always, not to mention Dan Weinstein, Robert Isaiah, Lawrence Schulman, and Michael Lavine.

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com; click here.

SING! SING! SING!

October 5: The BOBBY SHORT Centennial “Afro-Centric”

download: <or> play online:

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

Slouching Towards Birdland (Will Friedwald's SubStack) is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Terrific post. I'm a rocker but grew up with parents who loved Bobby Short and Garland so I'm very familiar with them (was taken to see Bobby in the early '70s, and knew Judy from my earliest memories of Wizard of Oz). We lived in the NYC area so of course I loved the song. My wife of many years is from New Jersey, and we still joke about the attitude New Yorkers like me grew up with!

What a deep dive! And yes, I too am curious as to how one sends a song by telegraph…

I’m researching Judy and this was a fun learning moment. Thx!