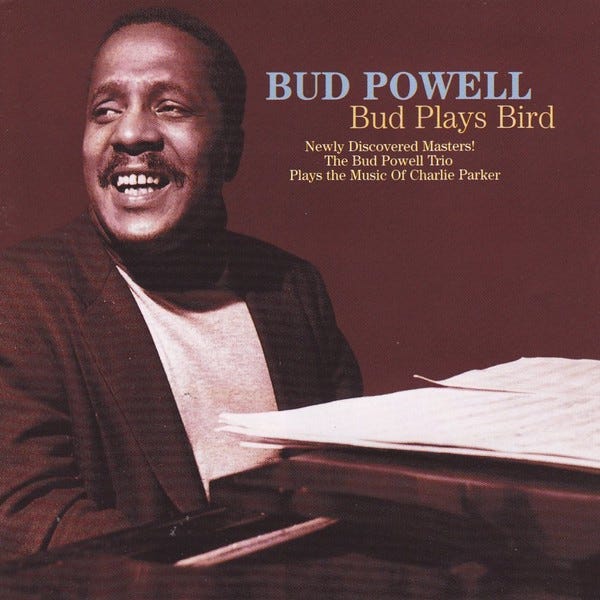

Bud Powell: "Bud Plays Bird" (1958)

from "Nights at the Red Steinway: Adventures in Jazz Piano"

This is one of several new pieces for my forthcoming book, Nights at the Red Steinway: Adventures in Jazz Piano, hopefully due later this year. I decided I needed a new essay on Bud Powell, and thought I would share it with everyone here as well. I regret that I haven’t had the opportunity to write about Powell that much over the years, he really is one of the most amazing players in the history of jazz. Special thanks once again to Bill Sando, of the American Pianists Association, for all of his help with this one, and to Elizabeth Zimmer, as always.

.Bud Plays Bird opens with Bud Powell stretching out on “Big Foot,” a 1948 blues by Charlie Parker, that was also recorded by the composer under the title of "Drifting on a Reed." The first thing we notice is that it’s fast, but not killer fast; that in itself is a surprise, or at least a challenge to our preconceived notions of Bud Powell’s music. Many listeners - most of all myself - tend to group pianists around their signature traits: I expect everything by Bud Powell to be fast, everything by Bill Evans to be lyrical, everything by Monk to be spacey, everything by Sun Ra to be outer-spacey, everything by Cecil Taylor to be weird, everything by Oscar Peterson to sound like five pianists on five separate keyboards all playing at once. Needless to say, they wouldn’t be real artists if they stuck to their calling-card approaches 100% of the time.

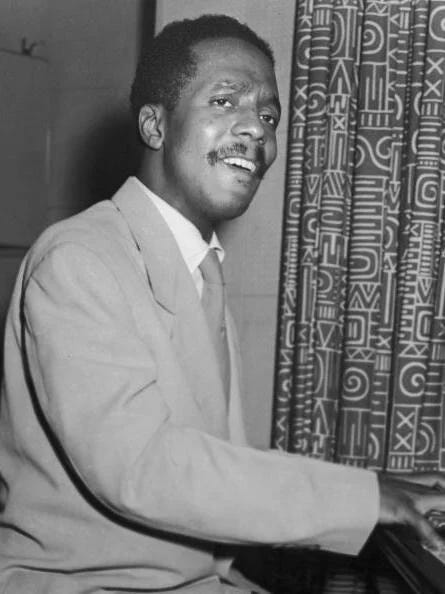

We associate Bud Powell with sheer speed because he was the piano poster child of the first generation of bebop, a music that distinguished itself from all the brands of jazz that had come before it both harmonically and rhythmically - as well as attitudinally. Part of the motivation for the creation of modern jazz was to devise a music that was so complex, so radically different from the swing and big bands styles that had come before it, that lesser musicians couldn’t even understand it, much less play it. At first, the public couldn’t make sense of it, either, but gradually the music became so widely accepted that it became the dominant mode of jazz; when a friend invites you to a jazz club, this is what you expect to hear. When colleges teach young musicians how to play jazz, it’s invariably bebop rather than swing or dixieland.

“Big Foot” is fast to be sure, but slower than a lot of Peterson or Art Tatum. Powell’s playing has a remarkable clarity to it. You hear the melodic lines in the right hand loud and clear, the chords and harmonic support in the left are never so dense as to distract from the improvised melody. In fact, that remarkable melodic transparency is as much a Bud Powell calling card as his usual sheer speed. And also, when the left and the right hands play in unison, that also suggests the single lines of a horn player - Charlie Parker in particular. And, as with other keyboard players, Powell’s humming - insomuch as the microphone picks it up - also adds another unison voice. He also benefits enormously from the very sympatico playing of his two trio associates, bassist George Duvivier and drummer Art Taylor.

Powell, Duvivier, and Taylor recorded the tracks that later become Bud Plays Bird over three sessions in October 1957, December 1957, and January of 1958, under the supervision of Roost Records house producer Rudy Traylor. It was Powell’s bad luck that somehow neither Roost nor Roulette Records got around to releasing them at the time; instead, they laid in the vaults until EMI acquired the Roulette-Roost catalog during the CD era, and were discovered and released by Michael Cuscuna in 1996. Bud Plays Bird is such a strong album that it would have done a lot for Powell’s already high reputation had it been released while he was still around to benefit from it, prior to his death at age 41 in 1966.

For one thing, Bud Plays Bird, is virtually the only “concept” or songbook album of Powell’s relatively short career - two of his final projects were tributes, respectively, to Thelonious Monk and Cannonball Adderley, but they’re not nearly as specifically focused and continually excellent as these 1957-’58 sessions. Which is only natural: Powell was the pianist most associated with Charlie Parker, the one who did the most to help crystalize the ideas of Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and company into keyboard form during Parker’s even shorter lifetime. At 15 tracks and nearly 70 minutes, Bud Plays Bird constitutes an abundance of riches, enough for two LPs at least; it’s almost as if Powell was somehow prescient enough to realize he was making a CD at least 30 years before the format was invented.

Drawing on works credited to Parker as a composer, the majority, starting with the opener “Big Foot” / "Drifting on a Reed," which is heard in two takes, both recorded at the same January session, although Mr. Cuscuna rightfully placed them at the beginning and end of the CD. “Buzzy” from 1945, was also originally in B flat but is, on the surface at least, a much more simple and hummable piece - I imagine neophyte musicians at Minton’s found it surprisingly complex. It was also part of the boppers’ modus operandi to take a relatively straightforward tune as a point of departure, and then weave all kinds of more complex lines in and out of it.

"Relaxin' at Camarillo,” a blues in C from 1946, was almost the opposite of “Buzzy,” it sounds dense and complex at first, but then swings in a relaxed way. The title was taken from Camarillo State Mental Hospital in California, and was inspired by Parker’s order court-ordained six-month stayed there in 1945-’46; a rare example of an artist or a celebrity of any kind, from that era in particular, acknowledging such a dark personal event. Powell’s treatment, however, is more “relaxin’” than anything else, with little to signify the presence of the inner demons that we know tormented both Parker and Powell. As Bill Sando puts it, “In order to give his right hand soloing clarity and a free rein, he uses chordally simple, limited and unintrusive comping techniques in his left.”

“Billie’s Bounce” is a much lighter tune with an appropriately lighter title and is, on the whole, a much more extrovertly swinging piece - like “Now’s The Time,” this is a Parker blues that could have been an R&B hit (as, indeed, “Now’s the Time” was, albeit under another title and credited to another composer); I can ready imagine Louis Jordan playing either one. Powell plays it like the bouncing boppish blues that it is. As before, he makes creative use of both his hands together playing in unison. Also in F, “Barbados,” has always sounded exotic to me, and as such is particularly ripe for Powell - here, he does more of his left-right unison playing, with a clean, uncluttered melody line - but then throws in a dash of spice via a major 7th leap upwards in the right hand melody line. “Barbados” is a close cousin to my favorite Powell original, his child-like calypso “Borderick” from his 1958 Blue Note sessions released as The Scene Changes album. Both tunes might be described as a halfway point between one of Bird’s many blueses and the calypsos like “Sly Mongoose” that Parkero also liked to play.

“‘Shaw Nuff,” credited to Parker and Gillespie, has also always sounded exotic to me, especially in its florid, vivid opening, although this very early (1945) bop head is based on the chord changes to “I Got Rhythm” rather than the blues. Now this is Powell at full speed ahead, ripping through the chords so fast it’s a wonder that even Duvivier and Taylor can keep up; just listening I have a hard time taking it all in. At a certain point he meanders through some different harmonies, some minor and flatted fourth colorings, and there’s also a well-done trade of fours with Duvivier and Taylor towards the climax. The other “rhythm”-based tunes here, “Moose the Mooche” and “Salt Peanuts,” are possibly even faster, with soaring, cleanly-articulated lines from the pianist. Both pieces also heavily feature Taylor, the first in a vivid trade with Powell.

"Scrapple from the Apple" which uses an “I Got Rhythm” bridge (the A-sections are based on “Honeysuckle Rose”) is another dense piece - heavy and light at the same time. Each note is actually a cluster, but there are crucial spaces between the notes, which are very clearly defined.

“Ornithology” is co-credited to the more obscure trumpeter “Little” Benny Harris, and is based on”‘How High the Moon,” a 1940 show tune that was already a jazz standard at the start of the transition into the modern jazz era just a few years later. It’s a case where the contrafact melody is as good as the original; between the moon and the avian activity referenced in the title of this variation, Powell’s interpretation is suitably high-flying and even soaring. “Ko-Ko,” Parker’s reworking of Ray Noble’s “Cherokee,” was a game changer in the development of modern jazz when first heard in 1945, and here it’s a vehicle for one of Powell’s fastest and most fleet-fingered takes.

“Confirmation” is certainly one of Parker’s most widely-heard “total” originals, a tune not based on an existing standard or even the blues. It’s another example of the lighter and brighter side of modern jazz. There’s a nod to his buddy, Thelonious Monk, with a few notes of “Well, You Needn’t” at 3:40.

“Dewey Square” also utilizes original changes; for all of Powell’s much publicized mental issues, the solos throughout here show the inherent logic of his conceptions; they sprawl out from the melody on a highly coherent basis, and make perfect sense musically and otherwise. There’s absolutely nothing here that suggests the product of a disordered mind. In fact, the whole album is like that - an album of bebop piano playing by one of the music’s all time masters, and at the very pinnacle of his powers.

Very Special thanks to the fabulous Ms. Elizabeth Zimmer, for expert proofreading of this page, and scanning for typos, mistakes, and other assorted boo-boos!

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here.

This week on Sing! Sing! Sing!: an interview with Hilary Gardner and an in-depth look at the phenomenon of “Country Music: Tin Pan Alley style,” which also happens to be the subject of my latest article this week in the Wall Street Journal, which you can read here.

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

The Amazing Bud Powell... The first Pianist I loved. Thanks for this, I'll try to find this album!

The R&B hit that incorporated "Now's The Time" into its melody was "The Hucklebuck" by Paul Williams, one of the most popular recordings in that genre in the 1950s.