“Artie Shaw: Time Is All You've Got” (playing at the Film Forum this weekend. On Sunday, January 7, film-maker Brigitte Berman will participate in a Q & A session with Film Forum’s Bruce Goldstein and the New York Sun’s Will Friedwald. For info, click here.)

Back in 1990, as a brash but not-yet-bald young man, this was one of my very first liner notes. It was a major honor when Sony Music assigned me to write up a half dozen or so entries in their Best of the Big Bands series. I eagerly wrote up Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman, not to mention Kay Kyser, and Les Brown and Ray McKinley, which was a delight in that I took the opportunity to interview the latter two. (For a compilation of Claude Thornhill, I had the chance to speak with Gerry Mulligan!)

Looking back on these more than 30 years later, I’m mainly astonished that Sony actually published all this verbiage - I wrote roughly 2600 words here.

"The past week has treated us to the spectacle of a hysterical young man throwing several hundred thousand dollars out the window." — Alton Cook

Artie Shaw is that most insidious kind of radical. At the zenith of his fame, he scraps the most popular band in the country — a veritable license to print money—to enjoy a few quiet drinks and loaf around down Mexico way. He insults his jitterbugging public, who made him rich and famous, by calling them a bunch of morons. He attacks the music industry, which transformed this shy, musically obsessed Jewish boy into a mega-celebrity sports hero/movie star equivalent, and tells the world it's a horde of panderers. He goes through so many wives in so few years that he threatens to ridicule and thereby undermine those dual institutions of our civilization known as marriage and divorce. Recalling Damon Runyan's observation that it's not so much a sin to gamble, but a sin to lose, Shaw then becomes the only man to challenge the great American dream who wasn't a hair-shirted lunatic hollering from a soapbox of sour grapes, but who had actually achieved what he mockingly called "$ucce$$," to the tune of several million dollars.

And yet, his most carefully planned act of conspiracy was a way of making music; later in his life he was able to articulate in ten words that are as deviously simple as the formula for an atom bomb: "playing the best possible songs in the best possible way."

The miraculous sound of all of Artie Shaw's orchestras; his near-genius as a clarinetist; the perfect swing, precision, and relentless flow of good ideas that never cease in his music; all have been analyzed technically and musicologically. Yet nothing could better describe how Artie Shaw changed the face of popular music for all time than Shaw himself in those ten little words.

Because, as straightforward as it sounds, no one had ever thought of it before; that is, the idea of viewing popular music as an art form. Where "concert jazz" bandleaders both earlier and later tried to pressure this music to trickle up into a higher-browed third stream (sort of reverse Reaganomics), Shaw argued and proved that it could be perfect in and of itself. And, defending himself against pundits on the other front, as blasters from the "hot" presses tried to force the notion that only the blues, and flag-waving (up-tempo) original jazz instrumentals, were suitable materials for big band swing, Shaw elicited his most passionate and hottest sounds from the utterly non-jazz sources of Broadway, Hollywood, and Tin Pan Alley.

Though his bandleading days were the shortest of any of the major leaders (off and on from 1936 to 1955, as opposed to the 50 years of incredibly prolific activity from Basie, Ellington, Goodman, Herman, and Kenton), it would be hard to imagine a musician who had a wider influence. Few other leaders never dared ape his band's style (in a period when even the distinctive sounds of Lunceford and Miller, for instance, were frequently imitated), musicians, and especially the great pop singers of the '40s on, starting with Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Peggy Lee, and Mel Tormé, acted very strictly according to the dictums set down by Rabbi Arshawsky.

It wasn't just Shaw's orchestral texture that caused Budd Johnson to describe his as "the first cool band," it was the attitude. Make the best music you possibly can, let nothing intimidate you and, yea, your righteousness shall exalteth you.

How do you get to be Artie Shaw? It's a long slow story painstakingly told by Shaw in his "outline of identity," The Trouble With Cinderella, which could have also been the script of a Frank Capra movie, with Shaw as class music's equivalent to Jefferson Smith, George Bailey or, most of all, Longfellow Deeds (whose nickname, "The Cinderella Man," also points directly to Shaw). An entirely self-taught individual, Shaw was the kind of artist you'd expect to be seduced by what were then considered the loftier reaches of culture, and at several points (both before and after being Midas-touched by the Goddess of Celebrity) in his life he sought to abandon the lucrative career of a studio musician and then a big-name movie-star-level bandleader to spend his time in vow-of- poverty academic and literary intellectual pursuits. How fortunate for us that he succumbed instead to what Noel Coward described as the potency of cheap music.

As laid down in Cinderella, Shaw, although born in New York in 1910, first won his wings playing with territorial bands all over the country, and then with the nationally known Irv Aaronson's Commanders. He had already taken at least one of his infamous sabbaticals by the mid-1930s; he turned to his regimen of studio work (which included important studio sessions with Red Norvo, Glenn Miller, and Frank Trumbauer) when he was asked to perform at an all-star swing concert on April 8, 1936, at the Imperial Theatre. (Above: a 1932 Vitaphone short starring Roger Wolf Kahn and his Orchestra with a 21-year-old Artie taking the hot clarinet solo on “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans.”)

Partly as a lark, Shaw composed "Interlude In B-Flat" for string quartet, jazz rhythm section, and his clarinet; it was so well-received that when the crowd demanded an encore, Shaw, having only assembled that one piece, had to play that same entire "Interlude"all over again.

A booking agent in the house, Tommy Rockwell, then got the notion of backing the handsome and charismatic Shaw as a touring bandleader; playing a clarinet even smoother than Benny Goodman (who later removed the rough "New Orleans" edges from his playing at least partially in response to Shaw's popularity) and leading a swing band with strings, he made a likely challenger for the Rockwell-O'Keefe Agency to send out as a rival to MCA's BG. According to Shaw, he only accepted on the grounds that once he made enough money to underwrite a literary career he would quit; eventually that's what happened, although Shaw didn't permanently turn off the money-making machinery until nearly 20 years later.

Rockwell landed them a steady spot at the Hotel Lexington in the summer of 1936, with regular broadcasts over CBS's WABC.. Most crucial for posterity, even before accepting Rockwell-O'Keefe's offer, Shaw had taken up a similar deal with the Brunswick Recording Company, thereby making the results of these June sessions (presumably done after at least a week of rehearsals) advance water-test indicators for what the agency felt was going to be a very major new band.

Shaw shows his determination to re-conceive the basic concepts of the orchestral jazz from his very first sides on, beginning most decisively with "The Japanese Sandman," the very tune which, through Paul Whiteman, had launched the initial vogue for jazz-tinged dance music back in 1920. (Similarly, Irving Berlin's "A Pretty Girl Is Like A Melody," premiered in the Ziegfeld Follies of a year earlier, and makes an auspicious debut for a maestro who could tell us all a few things about both melodies and pretty girls). Sammy Weiss, drummer on Shaw's first three dates, also seems to be commenting on acoustic-era (pre-Gene Krupa or Chick Webb) percussion styles, his oriental woodblock and pan-banging pointing to his later work with Mickey Katz on the famous "Bagle Call Rag."

"I Used To Be Above Love" and "No Regrets" also offer a throwback to earlier days of the dance-band biz in guitarist and unfortunate vocalist Wes Vaughn (infamous for his wimpy whining on Bix Beiderbecke's last records), who also underscores why Shaw preferred classy dames like Peg La Centra and waited until his 1946 teaming with the great Mel Tormé (who had grown up on Shaw records) before collaborating at length with any crooner. La Centra, one of the finer, albeit underappreciated “canaries” of the Lee Wiley-Helen Ward epoch (who also chirped on waxings by Johnny Green and Victor Young) unfortunately hit her career pinnacle in this Shaw band that never got off the ground, and never landed the one big record hit that would have brought her name before the public. (Most of Shaw's mega-sellers —"Begin The Beguine," "Frenesi," "Star Dust" — were, after all, instrumentals. Even Lena Horne and Helen Forrest, Little Miss Hitmaker herself, would only score their big chart-breakers with other bands).

Tony Pastor, whose relationship with Shaw parallels that of Jimmy Rushing and Count Basie, cuts his first vocals since their years with Aaronson on "One, Two, Button Your Shoe" and "Take Another Guess," and shows he's steadily developing into the hip-as-hell satchel-mouthed funster he would be in the '38-'39 Shaw band.

The strings supply, in Alfred Hitchcock's term, the "macguffin" or basic explanation of what this Jewish clarinet-playing swing bandleader had to offer that was different than that other Jewish clarinet-playing swing bandleader who had launched the swing band boom only a season earlier. Second-guessing the accusation that he's merely added strings to the standard Fletcher Henderson- Goodman band instrumentation, Shaw and chief arrangers Jerry Gray (playing violin) and Joe Lippman (on piano) use them both as a frontline section, like the brass and reeds, and also as support to the other sub-ensembles, like the rhythm section. To subvert any anticipated charges of effeteness that the fancy fiddles might engender, Shaw compensates by having the horns blast with an notably rough bravura (vastly different from his later translucent sound, retaining a touch of Dixieland polyphony, appropriately, on "Sugar Foot Stomp") Considering the expertise of the players, this must be construed as deliberate, even given their tender ages.

Shaw also disdains using the strings strictly as a fancy-shmancy velvet backdrop, as if he knew that this could quickly become a cliché. On some numbers, he lets his clarinet blend right in with them and become, in effect, the fifth fiddle; on "Darling, Not Without You," the transition from string ensemble to solo clarinet is so subtle you don't realize the violins have modulated down to the deeper registers. He also uses rhythm to separate the sections, as on "You're Giving Me A Song And A Dance," where the clarinet plays short staccato phrases atop the legato lines that only strings, not being dependent on human ventilation, can attain. On the whole, the violins work most effectively on the introductions, cagily playing rather obtuse lines designed to distract listeners into looking off in one direction as the horns sneak up and then go pow into the melody.

The string intro on the King Oliver-Louis Armstrong masterpiece "Sugar Foot Stomp" comes out of an especially distant left field, showing how '30s bandleaders were permitted greater liberties with the melodies of jazz or pop standards than for new tunes that song pluggers viewed as potential hits. On the whole, the dividing up of melodies into various segments as played by different sections or individual horns (the beautiful Bunny Berigan-style blasting of trumpeter Lee Castle, so effective on "Song And Dance," where he breaks out of the ensemble like Houdini liberating himself from so many ropes; Mark Bennett's and Buddy Morrow's trombones, and the Bud Freeman-influenced tenors, Tony Zimmer and Tony Pastor, also serve as effective solo voices) ties this first Shaw band most indelibly to the Henderson-Goodman model. However, while "South Sea Island Magic" includes none of the exotic effects that Shaw would later work into his depictions of faraway places with strange-sounding names, faint echoes of the band that would, two years later, stand America on its ear can be discerned, and not just faintly either.

Shaw was already orbiting around the conclusion he would ultimately land on, in which "each tune would more or less dictate the style of its own arrangement." Billie Holiday (who was no Wes Vaughn, thank God) must have provided the young bandleader with an object lesson as to how this could be achieved. In the middle of these sessions with his own first orchestra, he took time out to play on a session backing up the young singer, in the company of Bunny Berigan and Joe Bushkin, on a remarkable date that also included the Holiday classics “Summertime” and “Billie’s Blues” as well as another version of “No Regrets.”

As a bandleader, and a presenter - editor of arrangements, Shaw is beginning to come into his own even on his first sessions as a leader. The title says it all in "There's Something In The Air": just as La Centra's hum blends into her vocal like swirling particles of brain matter gradually becoming a thought (like that something in the air she's singing about), in the instrumental section, portions of the bouncy "Heart And Soul"-type vamp break off and become the central melody.

The most obvious indication of things to come occurs as a transition between the first and second chorus of the "The Skeleton In The Closet," written for Louis Armstrong in one of his first feature film appearances, Pennies From Heaven (1936). First, spooky, low-pitched strings and saxes (remarkable in that the discographies list no baritonist on this date) state the melody, then a ghastly aural apparition known as "Nightmare," Shaw's later opening and closing theme, appears in ghostly, skeletal form.

The first Shaw band started off well: after the Lexington, they switched to the French Casino while continuing to broadcast on WABC as often as three times a week, and recording a total of 31 songs over 10 sessions for Brunswick between June 1936 and February 1937. In December, the band played its first theatre engagement, at the New York Paramount; the showbiz bible, Variety, found the arrangements and jamming "slick" (they meant that as a compliment), but complained that they lacked "the change of pace and versatility necessary for stage work," although, they allowed, "for dance work it's probably something else again." The most bizarre observation concerned the increasingly dogmatic Shaw himself, later the chaser and the chase-ee of the most glamorous gals in moviedom, whom they accused of having "no personality!" (Anyone who knew Artie even remotely knew how ridiculous that assertion was!)

Throughout the remainder of 1936, with the band anchored in New York, Shaw could continue earning money as a sideman on studio dates with Bunny Berigan, Mildred Bailey, and, as mentioned above, Billie Holiday. However, leading a successful band meant touring, and that in turn entailed giving up this most significant part of his income.

Outside of New York the band's fortunes went straight downhill. At the Adolphus Hotel, in Dallas, business was so bad that the hotel chain canceled all subsequent engagements. After returning East on money from Shaw's pocket, their next gig, at one of the cradles of the big-time bands, Frank Dailey's Meadowbrook, wound up the same way (though at least Dailey knew a good band when he heard it and remained a friend and valuable contact for the leader).

Shaw then broke up his first band and formed a new one, which Brunswick Records immediately christened "Art Shaw and His New Music," to disassociate themselves from the strings-and-horns unit. He resolved that this new group would be "the loudest band in the whole goddamn world," but, perversely, he instead shaped it into the smoothest, most sophisticated, swingin'est, and the most musically satisfying (not to mention the most radical) band in the whole goddamn world. And, for a brief shining moment, the most popular.

That would be in the summer of 1938; by then, the beguine had begun, and with it, a new era in popular music. But a year earlier, when Shaw was forced to break up his visionary first orchestra, both he and lead arranger Jerry Gray were singing the blues. "It was such a great band," Gray cried to George Simon. "It broke my heart."

—Will Friedwald

Digital Producer: Michael Brooks

Digital Restoration and Engineering: Tim Geelan, CBS Records Studio, New York

Big Band Series Coordination: Mike Berniker, Amy Herot & Gary Pacheco

Packaging Coordination: Tony Tiller

Art Direction: Tony Sellari

Cover Art: Frank Driggs Collection

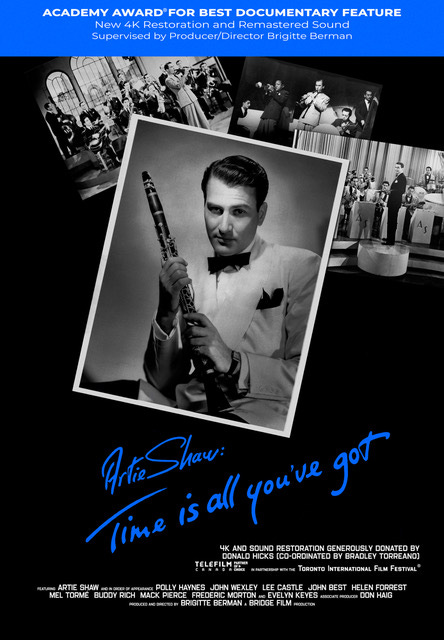

See you at the Film Forum on Sunday! In the meantime, here’s the newly-revised poster for Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got, sent to me by Ms. Berman. Yes!

Thanks to “Major” Tom Buckley for finding the CD booklet, which I had long since lost track of, and to David Garrick, for OCR-ing for me!

Very Special thanks to the fabulous Ms. Elizabeth Zimmer, for expert proofreading of this page, and scanning for typos, mistakes, and other assorted boo-boos!

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here

SPECIAL ENCORE PERFORMANCES!

December 31: The Early Years 1935-42 hosted by Will Friedwald

January 1: The Columbia Years 1943-’49 hosted by Ken Poston

January 2: The Radio Years: hosted by Chuck Granata

January 3: The Fall and Rise (1950-’54) hosted by Will Friedwald

January 4: Frank and Nelson hosted by Will Friedwald

January 5: The Capitol Years hosted by Loren Schoenberg

January 6: Bonus! Sing! Sing! Sing! Some Frank Conversation with Adam Gopnik

January 7: The Movies: Hosted by Chuck Granata

January 8: The Early Reprise Years 1960-'65 hosted by Loren Schoenberg

January 9:The Concert Years hosted by Ken Poston

January 10: The Rat Pack hosted by Ken Poston

January 11: Inside the Studio hosted by Chuck Granata

January 12: Bonus! In the Wee Small Hours with AJ Lambert (Sinatra’s granddaughter)

January 13: 1965-1974 The Main Event hosted by Will Friedwald

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

Hey, Will,

Do you think you could write up an article on Mildred Bailey sometime? Her voice fascinates me...