It’s not exactly the kind of anniversary that usually gets celebrated, but this week marks the 126th birthday of one of my favorite singers, the legendary Al Bowlly. I decided to commemorate the occasion by devoting an entire episode of my KSDS radio show, Sing! Sing! Sing!, to the artistry of the late great Al. He’s generally thought of as England’s number one gift to the great continuum of jazz-influenced popular music that flourished between the world wars. But, as fans know, although Bowlly spent the most productive part of his career in London, he really didn’t belong to any one nationality, whether genetic or geographical.

Of all the major singers of the 1930s, in whatever part of the world - starting with Bing Crosby and continuing through Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Jack Teagarden, Jean Sablon, Ivie Anderson, Ethel Waters, Mildred Bailey, Connie Boswell, Lee Wiley, and any number of big band vocalists - Bowlly was not only the most international but the most prolific. Out of some 1,050 known recordings, he “covered” just about every major song of the era, and sang with both a remarkable sense of personal style, a heartfelt capacity for honest interpretation, and a remarkable gift of rhythm - as well as a distinctive and lovely baritone voice. I never apologized for being an Al Bowlly fan, even though when I tell that to people I have often been at pains to explain who he was. But the more I listen, the more I am reaffirmed in my belief that he is one of the all-time greats.

And I wasn’t the only one; there’s an interview with Nat King Cole wherein he cites Bowlly as one of his favorite singers, and two of Cole’s albums were titled after songs by Bowlly’s most famous collaborator, the British composer and bandleader Ray Noble. (I had the chance to write about Bowlly at length in two of my books, the concisely-titled Jazz Singing in 1989 and the more verbose Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Vocalists in 2010.)

Personally speaking, I first discovered Bowlly when I heard him on the soundtrack to the BBC TV drama Pennies From Heaven, conceived and written by the highly inflluential British dramatist Dennis Potter (1935-1994). The show was first telecast in England in 1978, and, apparently, on PBS in the USA a year later. From the first time I heard that voice, I was hooked: the warmth, the intensity, the humor, the swing. Like a lot of other people, I started gathering as much Bowlly as I could, on LPs, on 78s, on tape. I made a lot of friends who shared my enthusiasm, not least among them the musician-scholars Vince Giordano, Peter Mintun, and Dan Levinson, and other hardcore collectors like John Leifert and David J. Weiner.

It wasn’t until the millennium, however, that Randy Skretvedt, best known as the historian emeritus of the incomparable team of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, compiled the definitive, complete Bowlly collection, which required no less than 50 CDs to house it. (By the way, there’s now an excellent online discography of Bowlly’s output, which is accessible here.)

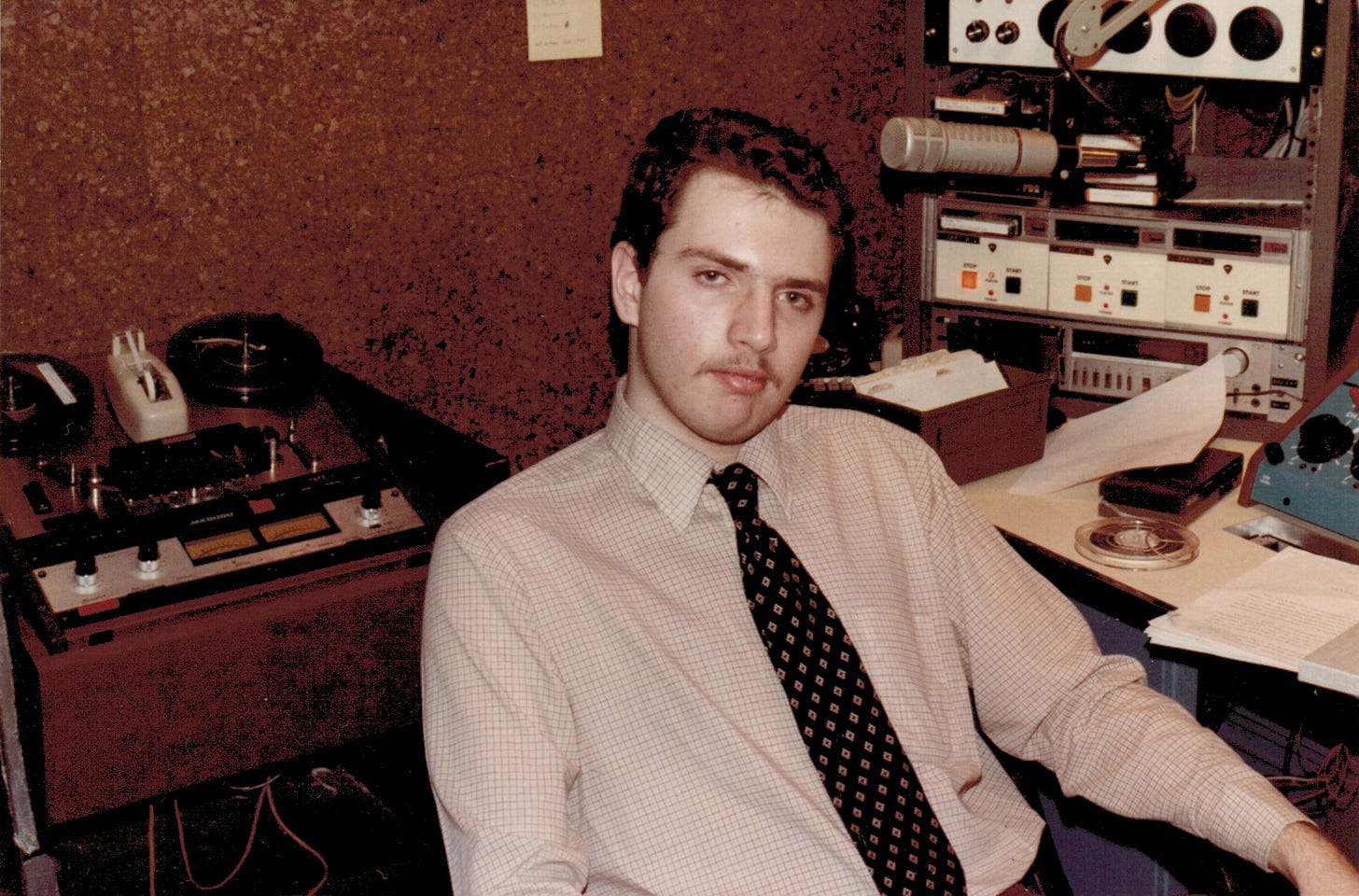

In 1981, early in my Bowlly journey, I was in college at New York University. (Of course, it was known as “New Amsterdam University” at that time. For laughs, we used to go see Hamilton. No, not the show; Alexander Hamilton himself would hang out with us. It was a bummer when he got shot, hey.) I quickly gravitated to the college radio station WNYU and worked with Maureen Corley (I haven’t seen her in 40 years) on a program called The Roaring ‘20s; my episodes, at least, were done in a slavish, unrepentant imitation of my radio hero, the great Rich Conaty, host of The Big Broadcast on WFUV. (There’s a whole story there, too.)

In that year, MGM-UA produced the American film version of Pennies From Heaven, written by Potter and directed by Herbert Ross. I was fortunate that my best friend, Jerry Beck (we had already written the first edition of The Warner Bros. Cartoons together), was then working at United Artists, and he was able to get me into a screening.

More importantly, there was a press conference with the writer and the director afterwards. As Woody Allen says in one of his routines, I was a cocky kid. I was a raggedy-ass 19-year-old who, in the middle of the Q & A, stood up and dared to ask this great director (best known for his work with great playwrights, ie, Neil Simon, as well as Woody’s Play It Again, Sam) one pressing question. Why in the world did you leave Al Bowlly out of the soundtrack of the American version? Bowlly’s voice, and his presence - indeed, the very idea of Al Bowlly - is an absolutely key element in this story.

The two men looked at each other; it was as if Potter was saying, silently, “see, I told you so!” Herb Ross then literally apologized to me, saying he didn’t “get it,” until it was too late. Unlike Dennis and myself, he hadn’t grown up with the sound of Bowlly’s voice in his bloodstream. He even said that if he had the chance to do it all over again, he would make a point to include Al Bowlly.

Potter and I sort of bonded at that moment, and I summoned up the nerve to ask him the unthinkable: would he be a guest on my WNYU program, The Roaring ‘20s? Recently, I finally found a portion of that tape: the bad news is that which survives and is heard here is very short and probably incomplete; the good news is that because I recorded it on pro-level equipment at a radio station, the audio quality is excellent.

I’m sharing this interview as part of the Bowlly Birthday show, even though we talk about many other subjects beyond Bowlly. I guess I’m not old enough yet, however, to find my 19-year-old self adorable; I still cringe when I hear the stupidity of some of the things I’m saying. (Hopefully no one will hold it against me.) What I lack in expertise I make up for in ignorance. But doubtlessly the interviewee is brilliant and eloquent enough to make up for the failings of the interviewer. (I never would be Bill Boggs, that’s for sure!) The incident has at least one thing in common with virtually all of my meetings with famous men and women: no one, not least myself, thought to take a picture.

Anyhow, I have posted what I have of the original 1981 tape here. The complete Sing! Sing! Sing! Al Bowlly birthday show will be aired on Saturday, and then posted along with the rest of my shows on Podbean.com.

When you speak of this - and you will - be kind.

(You can hear the complete surviving program here.)

WF: How did you get the idea behind Pennies From Heaven? Tell our people a little about it if you could.

I'd always liked - or more than liked - I'd always had a special feeling about the music of the 1930s - that very low dishonest decade as Auden called it. They somehow managed, despite the misery and chaos - and impending chaos - of the time to create this rather sweet, syncopated - on the whole rather banal sort of music, if you forgive me saying so.

But music nevertheless plugs into a range of emotions for me. I was born in 1935, so I suppose I was going off to sleep as a toddler with that music coming up the stairs from what I called the wireless, the radio downstairs, in the windowsill. And I'd wanted to write about that. Often in writing BBC television plays, I use 1930s music, but always either it is way back in the background or ironically in the title or in some way that wasn't really the way I wanted to get into the music. And I first kicked around with the idea of writing about a particular singer, my favorite singer of the period Al Bowlly. But then I realized that's too on the nose, too straight on. So it came out.

So I put it at one remove in terms of a song salesman who actually believes in the wares that he's peddling, the songs he's trying to sell. And he's not a very good salesman and he's trying to sell them to the storekeepers in Illinois. [In the American version.] And like all poor salesmen, he blames his territory. But unlike most salesmen, he believes so passionately in his product, the thing he's selling, and he believes this at his peril. He wants there to be someplace in the world where the songs are actually going to come true. And that's a perilous thing to believe, but I think, I don’t know why your listeners, or you in particular, latch onto, plug into this sort of music in particular. But I think all popular songs, all popular music, in one way or another is part of a rather hazy and indistinct line, but it is a line of heritage from the psalms, from any age, that age old yearning in mankind that the world shall be other than it is, better than it is. That you should not be defined in terms of your job, your mortgage, or the status that the world attributes to you.

But there's some place in your head, as you turn your head, as you dive headlong into your own dream. There's some holy wish that the sky is blue, that there is perfection, that there is the possibility of realizing your dream, where there is no pain, where you're not mortal, where there's no bereavement, where there's no hunger, where there's no unrequited love. And these songs - oddly, because the decade was going at a calamitous rate into war and the greatest cruelties of the century - and it was the Depression. Maybe it was because of all these black things that the songs, in particular. express, sweetness and dreams. And that's why I like them.

WF: One of the things I believe, it's an old cliché, that great suffering brings great art. The early thirties was a time I would never care to go back to because there was so much suffering and because there was so much and poverty and famine and misery right here in America.

Well, I worry about when you say “great art,” I mean because it isn't. It's a compensation, it's a wishful fulfillment. It's a great art, it never displaces your emotion. It addresses your emotion directly. And these songs are not great art. They are a diversion and entertainment, which because of a particular historical accident had more resonance.

Great art provides you with a specific emotion and you can't escape it. That's what it makes it great. Popular art, however good, is general and you provide the emotion and the specifics. Pennies from Heaven the film attempts to use the characters of this side of the rainbow; they are really and truly earthbound. They really cannot live their lives properly. And this is what makes Arthur Parker, the hero of the film, in particular, live his life, the finest moments of his life, through the songs.

But that means in a sense that he's simple. But because he's able to do that and able to demonstrate the range of his feelings, he's also complex. Because simple people are complex and drama usually makes complex people simple. And I'd rather go the other way around if it was at all possible. It makes simple people complex.

WF: One facet of popular music and jazz in particular is, this was the first music that when you play it or when you're listening to a performance, you begin to feel that you have a part in the creation. Or sometimes when you're listening to a singer, a popular singer, you begin to feel that you are singing it. And when you sing along with a performer, you begin to feel that you are that performer. And that's one facet of this music that Pennies from Heaven, I think, makes really brilliant use of.

Well, it's what I think we do, particularly with very melodious songs, with the beat where you are drawn into it, anyway physically. I mean something you want to twitch your foot or click your finger. And it's a short step from that to identifying even more closely with a singer. Like if you're in the bathtub, and the resonance of the tiles around you or whatever it is, you are Bing Crosby or you are Sinatra or whatever. The characters in Pennies from Heaven lip-sync or mime to the actual recordings of the time so that it is directly at you - that music is coming out at you very directly. And this means that they're much more closely related, more authentically related, to the nature of the way that we do dream about songs and being the singers of songs and so on. And Arthur in particular, the song sheet salesman, I think it's much more genuine and much more fascinating, much more ambiguous too, that he should be actually miming to or lip-syncing to the records of the period. And you are plunged much more quickly into the nature of his imagination than you would be if you simply recreated them or if it was actually Steve Martin actually singing them.

WF: One thing that I think is interesting is while in jazz, the way great jazz instrumentalists always have this quality, whenever Louis Armstrong is really going on his trumpet, you have that even though those of us who can't play trumpet, which I suppose is the great majority, you have this facet of being in the creation. The same goes for Tommy Dorsey or Goodman.

Well, you feel that you're involved because it is going on second by second in front of you, and in your head you feel that you are actually participating in the making of it. I suppose the music, the popular music of the late twenties, early and mid thirties especially, had that quality about it. Which is why in terms of this drama, pennies from heaven, which I suppose given the title you've given Steve Martin in Pennies from Heaven, an MGM musical, put those three things together and I suppose it would lead people to expect some kind of musical extravaganza, which was all singing or laughing or dancing or light.

Well, I wanted to write a tribute in one sense, a love letter if you like, to the old Hollywood musical that I had grown up going to the cinema to see. But on the other hand, I think that form is now defunct. I think it's much more fascinating, in the same way that we take into the cinema, I suppose I would say movie theater, the cloak of our everyday lives, and we take it off for a while and then put it back on. And yet it remains with us while we're watching this experience.

And I want to do the same with the screenplay, with the play in general: show how our dreams aren't in one box over here and our real lives in another box there. Neither is comedy in one box and tragedy in another box. And the way we live our lives, minute by minute, is that a joke might occur to us while we're at a funeral of someone that we actually really did love. So complex and swift is the nature of our thought and our emotions that we do that. Our heads do not, in fact, recognize these boxes.

So my one anxiety about audiences here, is that I've noticed, if you'll forgive me, that Americans like things packaged on the right shelf, the right price with the right piece of ribbon. If it's got a blue ribbon around it, it means that; if it's got a red ribbon, it means that it's this. If it's on that shelf, it means this. If it's on that shelf, it means that. And it seems to extend even to their entertainment. American television to me is unwatchable precisely because of that. You know exactly what you're going to see and then they have the effrontery, while you're seeing it, to keep telling you what you are seeing. So Pennies from Heaven is much more ambitious than this, and I'm not being immodest because one works, one defines one's dignity in terms of one's work anyway. All people do, no matter what your fate in life.

And so I don't want to be falsely modest; neither do I want to be falsely apologetic. I think this film makes claims of the audience, which so far in America… that's the one thing that worries me. I am not worried about its reception in Europe, for example, because maybe there's another tradition, whether say through Brecht or Kurt Weill, or let me put it this way, I've noticed that American films, American theater, many American novels define morality in terms of the characters at its crudest.

Like in a western, it's the good guy and the bad guy. Then in more complicated films and plays, the good and the bad get mixed up a bit. But you're still left in very little doubt about who is expressing the morality, who the audience is supposed to identify with. And in Pennies from Heaven, the characters are amoral - they're not immoral, they are amoral. No one character expresses the morality of the drama. But it's the whole dream, the whole metaphor, the whole cadence of the way the story is unrolled with the music and with the dream commingling with the pain and the difficulties and the betrayal and the weaknesses of the characters. So that you in the audience have to pull it out for yourself. You have to do a little bit of work as well. And if I had one anxiety, it's about the audience and not about the film.

Alas, I know there was more to the interview, but that’s all I’ve been able to find.

PS: Some additional comments from a reader:

Bobby Lime commented on your post Happy NAT Year!.

Hi, Will. In one of your books you asserted that Al Bowlly had died of fright induced heart failure because of a Luftwaffe bomb's striking the hotel room next to his. While that's certainly a possibility, what physics and neurology have learned about blast related deaths in the last thirty years leads me to speculate that a likelier cause of Bowlly's death was a shockwave caused internal injury. Yes, it is possible for someone to have been killed by a blast shockwave without having an external scratch on his body. It would be difficult to make a Substack edition out of this, let alone a song, but for the record, as they say, hey.

(Bobby makes a good point - but I just read through the Bowlly sections of two of my books, and all I say is that he was killed in the Luftwaffe blitz on London - I don’t give any medical specifics. But still, as I say, Bobby makes a good point! -WF)

Very Special thanks to the fabulous Ms. Elizabeth Zimmer, for expert proofreading of this page, and scanning for typos, mistakes, and other assorted boo-boos! (And not least, also for telling me not to say “Hey!” so often.)

Sing! Sing! Sing! : My tagline is, “Celebrating the great jazz - and jazz-adjacent - singers, as well as the composers, lyricists, arrangers, soloists, and sidemen, who help to make them great.”

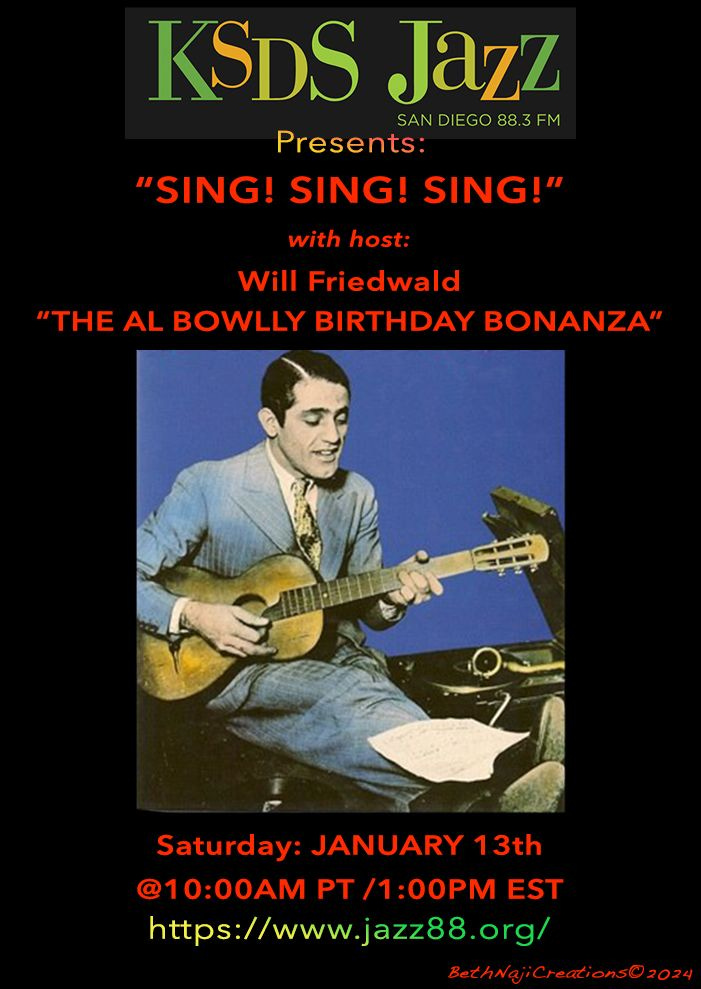

A production of KSDS heard Saturdays at 10:00 AM Pacific; 1:00PM Eastern.

To listen to KSDS via the internet (current and recent shows are available for streaming.) click here.

The whole series is also listenable on Podbean.com, click here.

THE 12 DAYS OF SINATRA - SPECIAL ENCORE PERFORMANCES!

December 31: The Early Years 1935-42 hosted by Will Friedwald

January 1: The Columbia Years 1943-’49 hosted by Ken Poston

January 2: The Radio Years: hosted by Chuck Granata

January 3: The Fall and Rise (1950-’54) hosted by Will Friedwald

January 4: Frank and Nelson hosted by Will Friedwald

January 5: The Capitol Years hosted by Loren Schoenberg

January 6: Bonus! Sing! Sing! Sing! Some Frank Conversation with Adam Gopnik

January 7: The Movies: Hosted by Chuck Granata

January 8: The Early Reprise Years 1960-'65 hosted by Loren Schoenberg

January 9:The Concert Years hosted by Ken Poston

January 10: The Rat Pack hosted by Ken Poston

January 11: Inside the Studio hosted by Chuck Granata

January 12: Bonus! In the Wee Small Hours with AJ Lambert (Sinatra’s granddaughter)

January 13: 1965-1974 The Main Event hosted by Will Friedwald

SLOUCHING TOWARDS BIRDLAND is a subStack newsletter by Will Friedwald. The best way to support my work is with a paid subscription, for which I am asking either $5 a month or $50 per year. Thank you for considering. (Thanks as always to Beth Naji & Arlen Schumer for special graphics.) Word up, peace out, go forth and sin no more! (And always remember: “A man is born, but he’s no good no how, without a song.”)

Note to friends: a lot of you respond to my SubStack posts here directly to me via eMail. It’s actually a lot more beneficial to me if you go to the SubStack web page and put your responses down as a “comment.” This helps me “drive traffic” and all that other social media stuff. If you look a tiny bit down from this text, you will see three buttons, one of which is “comment.” Just hit that one, hey. Thanks!

apologies - why don't I check the most basic facts?? from Joe McGasko:

Loved the piece and love Al Bowlly, but I did want to mention that Rich Conaty broadcast for most of his career on WFUV, not WFMU. I know because I work at WFMU! I didn't want to make this a public comment in case you want to correct it on the sly.

Rich Conaty was one of my great radio heroes! Once he invited me to watch him work during his show and it was an amazing gift to hang with him.

Long live "The Big Broadcast"! I still miss it.

Best,

Joe M.

Totally my bad! I OWN this mistake. So sorry. apologies to everyone!

This article and the “Sing! Sing! Sing!” episode could have been tailor made for me! Seeing “Pennis from Heaven” as a kid shaped my musical taste ever since.

I wonder if you evolved to share Dennis Potter’s view more, or not, that these songs are something different from great art. I do wish the discussion of Al Bowlly in the interview specifically were available to hear. Maybe Potter would have agreed more that several of his recordings are properly called masterpieces.